1931 – Breakdown and Brinkmanship

A Nation Slipping Further

By 1931, the Great Depression was no longer a downturn. It was a national breakdown. With unemployment soaring, banks failing, and political paralysis deepening, the United States entered a darker phase—marked not just by financial collapse but by institutional failure and mounting despair.

“The difference between 1930 and 1931,” writes Dr. Helena Markov of Defined Benefits, “is the disappearance of illusion. By 1931, almost no one still believed the storm would pass quickly.”

Unemployment Becomes a Crisis

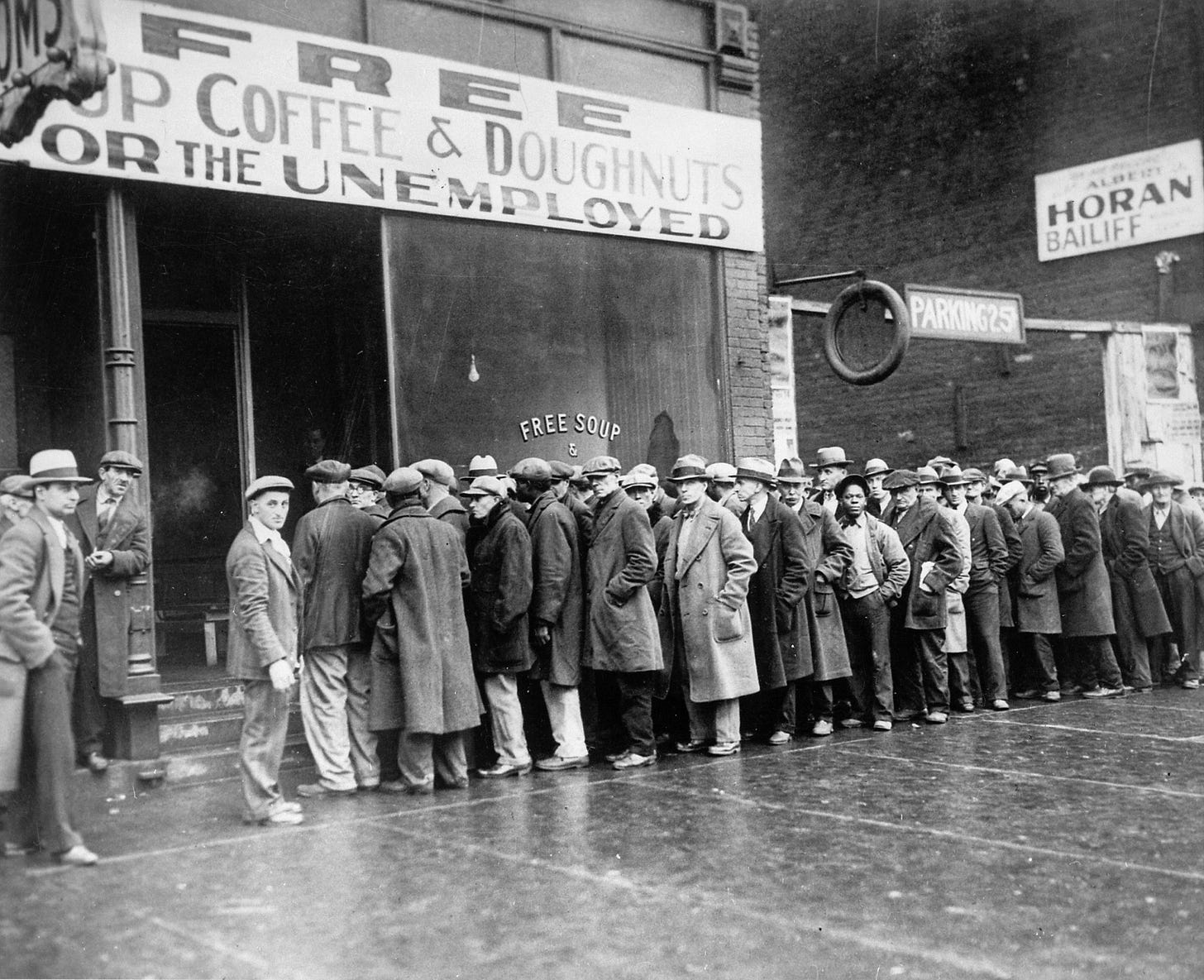

By the end of 1931, unemployment reached 15.9%, with over 8 million Americans out of work. In major cities like Cleveland, Toledo, and Detroit, the rate approached or exceeded 30%.

Factory closures accelerated. In New York City alone, over 200,000 jobs were lost. Industrial production dropped by nearly 15% over the year, continuing the steepest peacetime economic contraction in U.S. history.

The personal toll was staggering:

Men lined up for hours hoping to get day labor.

Women and children scavenged for food.

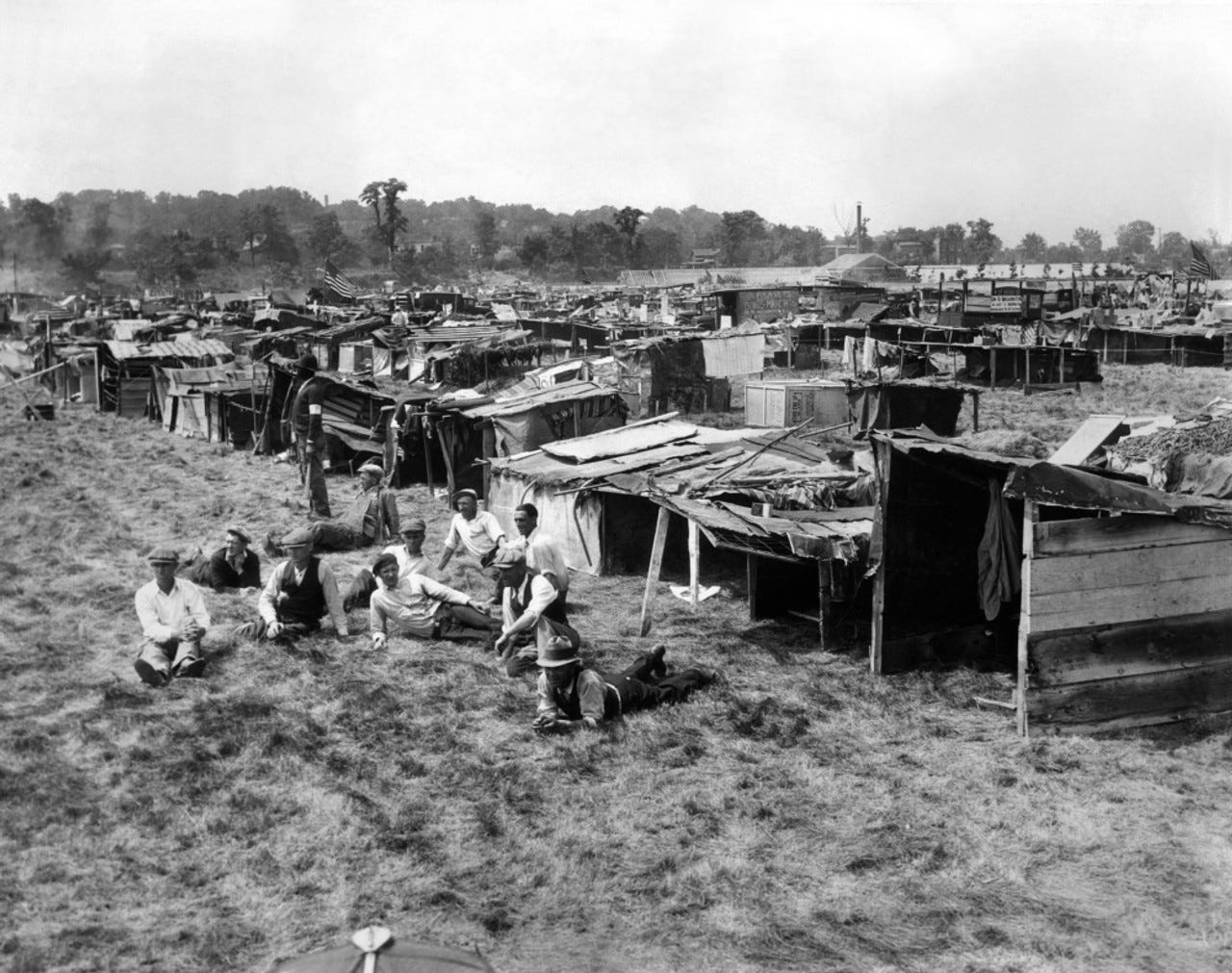

Families moved into “Hoovervilles”, now found in almost every major city.

Banking Crisis Explodes

While 1930 saw bank failures, 1931 turned it into a systemic collapse.

Over 2,300 banks failed in 1931, more than double the number from the year prior. Depositors lost nearly $390 million in savings. With no FDIC, people rushed to withdraw their funds wherever they feared collapse—triggering runs on banks across the country.

The ripple effects were devastating:

Credit froze, making business recovery impossible.

Farmers lost access to loans and equipment.

Confidence in local and regional banks evaporated.

Professor Leon Briggs of Defined Benefits notes: “1931 showed how critical trust is in finance. Once Americans lost trust in the banks, even solvent institutions were dragged under.”

Global Reverberations: The European Crisis

While the U.S. economy was imploding, Europe’s financial system also collapsed, tightening the depression's global grip.

In May 1931, Austria’s largest bank—Creditanstalt—collapsed, setting off a chain reaction in Germany and across Europe. Britain was forced to abandon the gold standard in September. International lending dried up.

U.S. exports plummeted. Global trade shrank by over 20% in a single year.

Hoover’s response came in the form of the “Hoover Moratorium”, a one-year suspension of German reparations payments. But it was too little, too late. The world economy was unraveling faster than diplomacy could patch it together.

The Rise of Defiance: Hunger Marches and Protests

1931 saw the beginning of organized resistance to the depression’s effects.

Veterans’ protests began foreshadowing the Bonus Army of 1932.

Hunger marches erupted across cities like Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, and Washington, D.C., organized by unemployed councils and socialist groups.

Tenant protests challenged evictions, with neighbors forcibly moving evicted families back into their homes.

In Detroit, Ford workers led a massive protest against wage cuts, which police and company guards met with violence.

“These weren’t just breadlines anymore,” Dr. Markov writes. “1931 was when suffering turned political.”

Hoover’s Inertia and Isolation

As the economy worsened, President Hoover’s unpopularity deepened. His approach—marked by faith in business, voluntary cooperation, and balanced budgets—now appeared out of touch.

He refused direct relief, fearing it would create dependence, and instead pushed for more loans to banks and businesses, via the newly authorized Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC).

But this trickle-down approach failed to address the immediate suffering. Cities ran out of welfare funds. Private charities were overwhelmed. In many places, there was no help at all.

“Hoover wasn’t a villain,” says Briggs, “but he was paralyzed by his own ideology. He couldn’t see that the old rules no longer applied.”

Agricultural Collapse and Suicide Rates

Farmers faced a year of utter devastation. Crop prices dropped even further—corn sold for less than the cost of firewood, and many Midwestern families burned their crops to stay warm.

Farm foreclosures surged. Many farmers walked away from their land. Entire rural counties became debt-ridden ghost towns.

Worse, suicide rates rose sharply—particularly among formerly middle-class professionals and farmers. In cities and small towns alike, the despair was not just economic. It was existential.

Corporate Collapse and the End of the Roaring Twenties

By 1931, many of the companies that had symbolized the 1920s boom were in trouble.

General Motors slashed wages and shuttered plants.

Radio Corporation of America (RCA), once the darling of investors, saw its stock fall over 90% from its peak.

U.S. Steel and other industrial giants reported record losses.

Wall Street itself became a graveyard of broken dreams. By December 1931, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was down nearly 90% from its high in 1929.

Culture in Crisis

Despite the darkness, 1931 was a powerful year for cultural response to the depression.

Films like City Lights (Chaplin) and Frankenstein offered both escape and metaphor.

Langston Hughes, Carl Sandburg, and other writers captured the anguish and resilience of ordinary Americans.

Gospel, blues, and early country music began to echo themes of loss, hunger, and endurance.

Photographers—some funded by early public arts projects—began documenting soup lines, child labor, and foreclosure signs.

Seeds of Change

As 1931 came to a close, political pressure began to mount. The 1930 midterms had already handed the Democrats more seats in Congress. By the end of 1931, governors, mayors, and newspapers were openly criticizing the president.

Meanwhile, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Governor of New York, launched a state relief program, experimenting with jobs programs and food assistance. His growing visibility as a voice for action foreshadowed the coming political shift.

“There was no New Deal yet,” Markov writes, “but 1931 was when Americans started looking for one.”

1931 – The Point of No Return

If 1929 was the crash and 1930 the slide, 1931 was the freefall. It was the year that tested American resilience, shattered long-held assumptions about capitalism, and exposed the limits of voluntary aid and state inaction.

Unemployment doubled. Banks collapsed. Suicides spiked. Protest grew.

And while Hoover clung to the past, the people were starting to imagine a different future—one that would demand federal action, not faith alone.

“By the end of 1931,” says Professor Briggs, “the nation was no longer waiting for recovery. It was waiting for a new direction. The old America had broken. What came next would be built from desperation and imagination.”