1932 – The Breaking Point

Desperation Becomes the Default

By 1932, the United States had entered the deepest and bleakest phase of the Great Depression. Economic collapse had hardened into social crisis. Every institution—government, banks, industry—was under strain. Confidence was gone. Hunger was common. Violence felt near.

“This was the year when everything cracked open,” writes Dr. Helena Markov of Defined Benefits. “By 1932, survival—not recovery—was the goal for millions of Americans.”

The Worst Year Economically

No year in American history before or since has matched the economic devastation of 1932.

Unemployment peaked at 23.6%, leaving over 12 million Americans jobless.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell 13.4%, on top of massive declines from the previous two years.

5,100 banks failed, taking with them over $3 billion in deposits.

Stock market values were down nearly 90% from their 1929 peak.

Business failures skyrocketed. Entire sectors—steel, auto, textiles—were operating at a fraction of their 1928 capacity. Deflation made even falling wages feel like raises—until more layoffs came.

Families skipped meals. Children dropped out of school. Men traveled hundreds of miles for rumors of work.

Hoover’s Final Year: Paralysis and Protest

President Herbert Hoover, nearing the end of his term, maintained a rigid belief in voluntary cooperation, local relief, and balanced budgets. But the public had long lost faith.

He vetoed multiple bills that would have provided direct federal aid to the unemployed, fearing dependence and undermining American values.

His largest move—backed by Congress—was expanding the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which lent money to failing banks and large businesses. Yet these moves were viewed by the public as helping Wall Street over Main Street.

Professor Leon Briggs of Defined Benefits observes:

“Hoover may have acted more than history gives him credit for—but his actions missed the political moment. People were starving while banks got lifelines.”

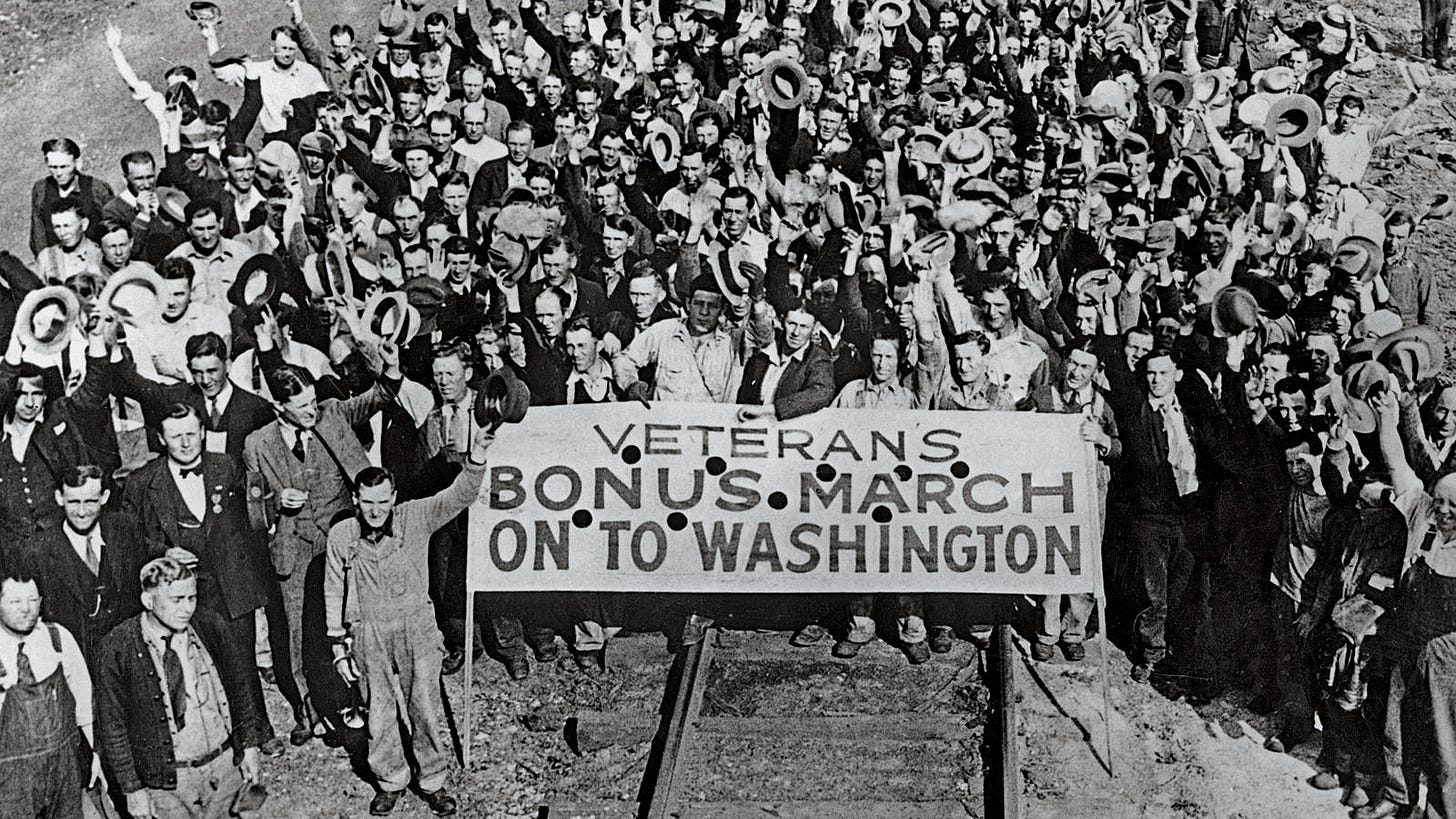

The Bonus Army: Protest Turns Violent

The most defining event of 1932 was the Bonus Army march.

Over 20,000 World War I veterans and their families camped in Washington, D.C., demanding early payment of bonuses scheduled for 1945. They built shantytowns, held peaceful demonstrations, and lobbied Congress.

But Congress rejected the bonus payment.

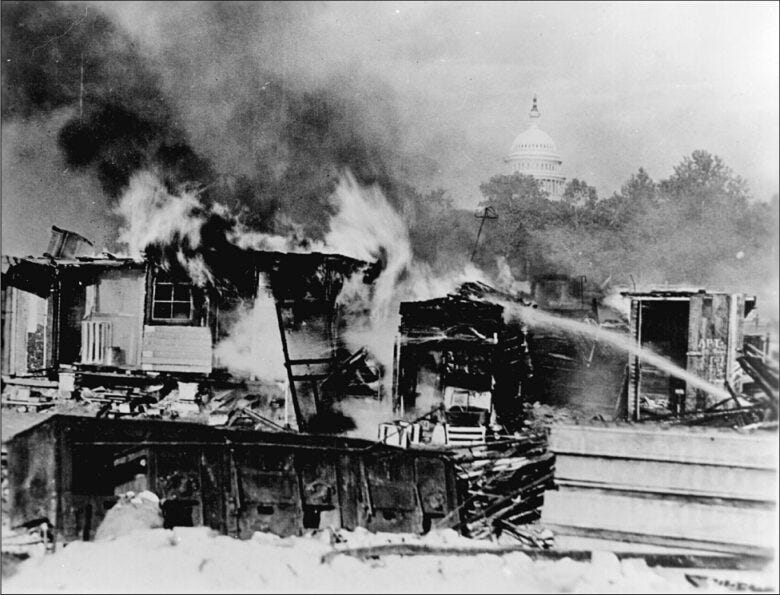

In late July, Hoover ordered the U.S. Army, led by General Douglas MacArthur and assisted by Dwight D. Eisenhower and George Patton, to disperse the protest.

Troops used tear gas, bayonets, and cavalry charges. The camps were burned. One infant died. Dozens were injured. Newspapers nationwide published photos of soldiers attacking veterans.

The Bonus Army debacle devastated Hoover’s reputation.

Hunger and Homelessness Intensify

Food insecurity became dire. Breadlines stretched for blocks in every major city. Churches and charities were overwhelmed.

By mid-1932:

In New York, 1 in 4 families required relief.

In Chicago, thousands lived in freight cars and under bridges.

In rural Mississippi, teachers reported students fainting from hunger.

Suicide and alcoholism rates continued to rise.

Shantytowns known as “Hoovervilles” now sprawled across the nation—from Central Park in New York to Seattle’s waterfront.

In the winter of 1932, many froze to death sleeping outdoors or in unheated homes.

The Rise of Mutual Aid and Radicalism

With government support absent or inadequate, Americans turned to each other.

Barter networks replaced cash economies.

Unemployed councils helped resist evictions and organize rent strikes.

Food co-ops emerged.

In some cities, mobs looted grocery stores out of desperation.

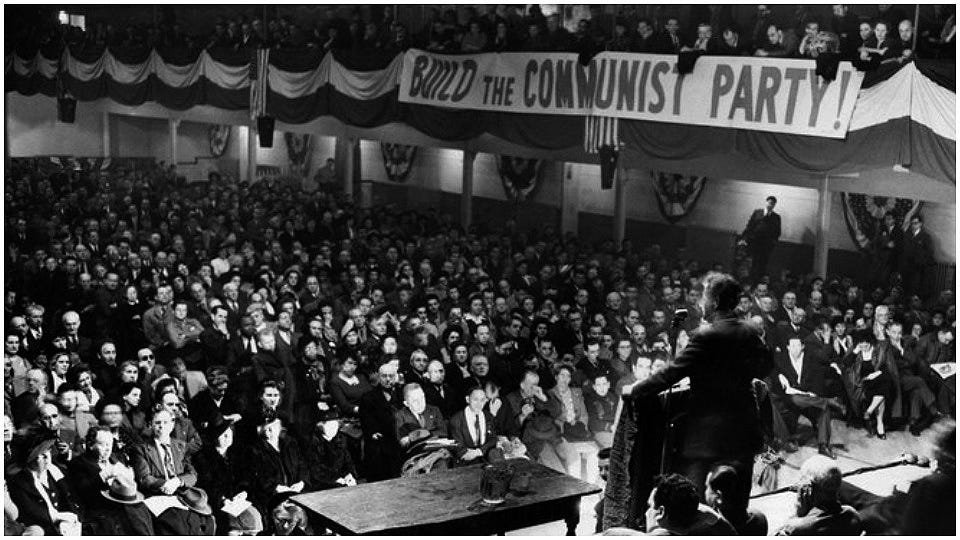

At the same time, radical politics gained traction:

The Communist Party organized marches, factory sit-ins, and hunger protests.

Socialist leaders gained prominence in cities like Milwaukee and New York.

Labor unions began to regroup despite hostile environments.

Desperation bred both solidarity and militancy.

Cultural Echoes of Collapse

Despite the bleakness, 1932 was a pivotal year culturally.

Photographers like Dorothea Lange began documenting urban and rural poverty.

Langston Hughes, John Steinbeck, and Richard Wright began writing about the Black and working-class experience.

Radio became a refuge, as families gathered around to hear sermons, jazz, and serialized drama.

Hollywood offered escapism with films like Grand Hotel and Scarface, even as it subtly mirrored themes of corruption and survival.

FDR’s Campaign and the Call for Change

As the 1932 election approached, the political mood shifted dramatically.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Governor of New York, emerged as a national figure promising “a new deal for the American people.” He spoke of bold government action, relief, and public works—not trickle-down economics.

His campaign emphasized:

Direct aid to the unemployed.

Job creation through public investment.

Banking and financial reform.

Agricultural supports and mortgage relief.

Americans responded in droves.

In November 1932, Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a landslide—winning 42 of 48 states.

Briggs explains:

“1932 wasn’t just a change in leadership. It was a rejection of the old system. People were done waiting. They demanded action.”

Toward the New Deal

Though Roosevelt would not take office until March 1933, his victory gave hope.

Across the country, local Democratic leaders began preparing plans for infrastructure projects and relief programs. Unions sensed opportunity. Journalists wrote of a “Roosevelt Revolution.”

But the interregnum—those four months between election and inauguration—proved dangerous. Banks continued to collapse. Unemployment ticked higher. Roosevelt refused to take action until in office.

The final months of 1932 felt like the eye of the storm—full of silence, tension, and the dread that more collapse was still ahead.

Conclusion: 1932 – Collapse Meets Turning Point

1932 was the darkest year of the Great Depression, the nadir of American economic, political, and social life. But it was also a year of political awakening and a decisive break with the past.

The Bonus Army had marched. The public had protested. And the people had spoken at the ballot box.

Dr. Markov concludes:

“1932 was the bottom. But it was also the year Americans began to imagine something different. Not just recovery—but redefinition.”

From the ashes of 1932 would rise the most transformative political era in American history. But first, the country had to survive its collapse.