1933 – The Year America Fought Back

From Collapse to Turning Point

By January 1933, the United States stood on the edge of economic and social collapse. One in four Americans was unemployed. Thousands of banks had failed. Industrial output had cratered. Hunger, homelessness, and hopelessness defined daily life. But unlike the previous years, 1933 marked a turning point—when the federal government, under newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt, began to act decisively.

“1933 was the year the nation decided it would not perish in silence,” writes Dr. Helena Markov of Defined Benefits. “It was the year desperation collided with determination.”

The Final Days of Hoover

In the last months of Herbert Hoover’s presidency, the country was in free fall. The lame-duck president remained committed to policies of voluntary cooperation, fiscal austerity, and trickle-down loans. The banking system, however, was collapsing outright.

Between January and early March, more than 4,000 banks closed their doors, wiping out billions in deposits and shutting off credit to towns and businesses across the country. States like Michigan declared banking holidays, essentially freezing financial activity to prevent total collapse.

Protests and unrest grew more intense. In several states, farmers formed “Holiday Associations,” blockading roads and threatening violence to stop foreclosures and livestock seizures. Angry citizens surrounded courthouses and clashed with police.

By March 1933, America’s economy had ground to a halt. The stock market was barely functioning. Cities couldn’t pay teachers or police. Over 13 million Americans were unemployed. Hunger riots broke out in several cities. It was arguably the lowest point in modern U.S. history.

The Inauguration of Hope: March 4, 1933

On March 4, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the oath of office. His speech, delivered to a frightened but hopeful nation, began with one of the most famous lines in American political history:

“The only thing we have to fear is… fear itself.”

His inaugural address was direct, confident, and radical in tone. He spoke of putting people to work, reforming the banking system, and attacking the Depression “as we would a foreign foe.” It was not just a change of leadership—it was a change of tone, urgency, and moral commitment.

“Roosevelt didn’t just promise new policies—he promised a new relationship between the government and the governed,” says Dr. Leon Briggs of Defined Benefits. “That’s what made 1933 revolutionary.”

Emergency Banking Act and the “Bank Holiday”

Roosevelt’s first major act was to declare a nationwide bank holiday, shutting down all banks temporarily to stop the financial hemorrhage and allow federal inspection.

On March 9, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act—within hours of its introduction. The bill allowed solvent banks to reopen and provided federal backing to restore public confidence.

Roosevelt then took to the airwaves for his first Fireside Chat, explaining the banking crisis to the American people in plain language. He asked for their trust and cooperation. It worked.

When banks reopened on March 13, millions of Americans returned their money to the banks. The immediate banking panic was over.

The Hundred Days: Legislative Blitz

From March to June 1933, Roosevelt and Congress launched the most intense legislative period in U.S. history, known as the Hundred Days. In that short span, Roosevelt signed 15 major pieces of legislation, laying the foundation of the New Deal.

Key acts included:

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) – Employed hundreds of thousands of young men to work in forests, parks, and public lands.

Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) – Sent direct aid to states and cities to provide relief and create jobs.

Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) – Aimed to raise crop prices by paying farmers to reduce production.

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) – Created a massive public works and energy development program in the South.

National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) – Established codes for fair labor practices and authorized the Public Works Administration (PWA).

Glass-Steagall Act – Separated commercial and investment banking, and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

This avalanche of policy represented a seismic shift in the federal role. Washington, for the first time, was actively managing capitalism, providing jobs, securing banks, and protecting the public interest.

Relief, Recovery, and Reform

Roosevelt’s New Deal focused on three Rs:

Relief: Immediate support for the unemployed and poor.

Recovery: Efforts to restart economic growth.

Reform: Structural changes to prevent future crises.

In 1933, most efforts concentrated on relief and recovery. The creation of the CCC and FERA provided work and hope. By December, over 2 million Americans were employed in New Deal programs.

Families that had lived in Hoovervilles or rail cars now had basic wages, meals, and stability. The emotional impact was as important as the economic one.

Briggs notes:

“New Deal programs weren’t just jobs—they were public commitments. Americans saw the government, for the first time, on their side.”

Rebuilding Confidence

Confidence, so central to economic functioning, began to return. Consumer spending slowly improved. Farmers, supported by subsidies and price supports, began planting again with hope of profitability. Banking deposits stabilized.

The stock market rebounded, with the Dow Jones gaining over 60% during the year.

Although unemployment remained painfully high, and the Depression far from over, 1933 was the first year since 1929 that did not feel like a descent into further chaos.

Opposition and Limits

Not all was smooth. Business leaders bristled at Roosevelt’s interventionist policies. Conservative newspapers decried the growing size of government. The Supreme Court would later challenge the legality of several New Deal programs.

The AAA, for example, sparked outrage when crops were destroyed or left to rot while Americans starved. Labor unrest simmered beneath the surface, and racial and regional inequalities persisted.

New Deal programs also disproportionately excluded Black Americans and Mexican immigrants, either through local discrimination or federal neglect.

Roosevelt’s team, though well-intentioned, had blind spots that would only be partially corrected in later years.

Cultural Shifts

1933 also witnessed cultural responses to the shifting times.

Dorothea Lange began photographing migrant workers in California.

Woody Guthrie traveled through Dust Bowl towns, writing songs of sorrow and survival.

The radio era exploded, giving rise to shared national experiences through Roosevelt’s chats, serialized dramas, and news broadcasts.

In literature, writers like John Dos Passos and James T. Farrell chronicled working-class life and alienation.

The idea that Americans could share both pain and hope began to shape the country’s cultural identity.

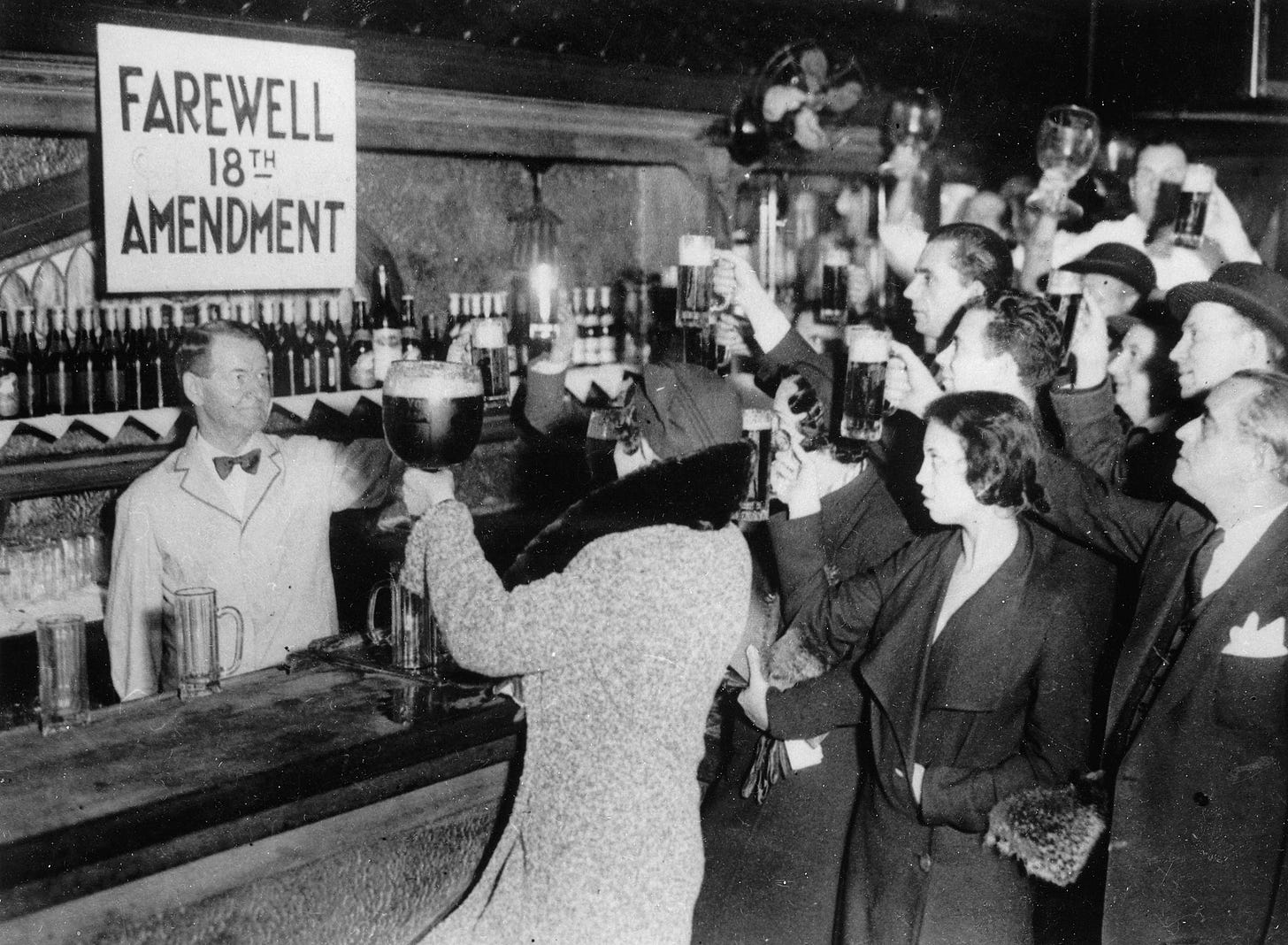

End of Prohibition

In December 1933, one of Roosevelt’s most popular reforms took effect: the 21st Amendment, repealing Prohibition.

The end of the 13-year alcohol ban brought:

New tax revenues

Jobs in brewing and hospitality

Relief to millions tired of bootlegging and black markets

It also marked a philosophical shift—government now responding to the practical will of the people, not moral purism.

A Year of Bold Beginnings

1933 was not a year of economic salvation—but it was a year of political courage, public engagement, and foundational change.

After three years of freefall, Americans saw a government acting rather than pleading. They saw policies taking root rather than excuses being offered. They saw hope return—not from markets, but from mutual effort.

“1933 proved that democracies can respond to crisis without falling into dictatorship,” Dr. Markov concludes. “That may be its most enduring legacy.”

Roosevelt’s New Deal would evolve and expand over the next several years, but it was in 1933 that the blueprint was drawn—and the long climb out of the Depression truly began.