1936 – The New Deal Defended

From Crisis Management to Political Consolidation

By 1936, the United States was still in the grip of the Great Depression—but no longer in free fall. Major New Deal programs were operational, and confidence was returning. While unemployment hovered around 17%, it had improved from the darkest days. America was rebuilding—not just roads and bridges, but faith in its future.

“1936 was the year Roosevelt asked the country not just to endure the New Deal, but to endorse it,” writes Dr. Helena Markov of Defined Benefits. “It was a national referendum on whether government should protect the weak—or stand back.”

A Year of Uneven Economic Recovery

The economy in 1936 was improving:

GDP grew by nearly 14%—the strongest annual growth since the Depression began.

Industrial production surged.

Wages rose modestly.

The stock market rebounded.

Federal programs employed millions through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and Public Works Administration (PWA).

Still, challenges persisted:

Unemployment remained in the double digits.

Rural poverty was still severe, especially in the South and Midwest.

The Dust Bowl, though beginning to ease, continued to displace thousands.

Many Americans remained one illness, one job loss, or one foreclosure away from ruin.

But for the first time in nearly a decade, people felt like the country was moving forward.

The 1936 Election: New Deal on Trial

The defining event of the year was the presidential election. Franklin D. Roosevelt sought re-election on the strength of the New Deal. His Republican opponent, Governor Alf Landon of Kansas, was a moderate conservative who criticized the inefficiency and cost of federal programs but accepted some aspects of the New Deal.

Roosevelt’s campaign, however, was more than policy—it was a message:

“This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.”

He painted the election as a choice between an active, compassionate government and a return to laissez-faire policies. He took on business elites, Wall Street, and monopolies, famously declaring:

“They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

Professor Leon Briggs of Defined Benefits observes:

“1936 was the first modern political campaign centered on economic justice. Roosevelt didn’t just defend the New Deal—he weaponized it.”

A Landslide Like No Other

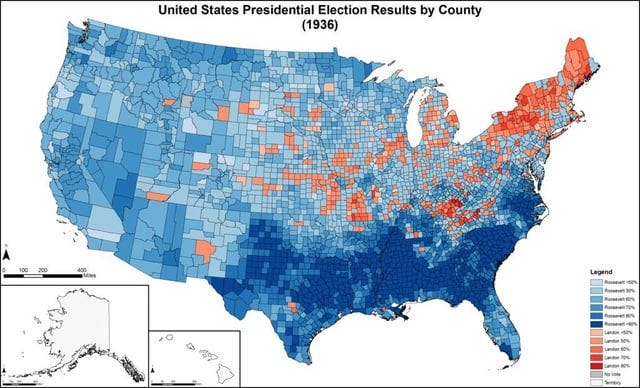

The public overwhelmingly sided with Roosevelt.

FDR won 60.8% of the popular vote—the highest since 1820.

He carried 46 of 48 states, losing only Vermont and Maine.

Democrats expanded their congressional majorities, holding over 75% of seats in both chambers.

This victory was a mandate—not just for Roosevelt personally, but for the philosophy of the New Deal. It reshaped American politics for generations.

The New Deal Coalition Takes Shape

The 1936 election solidified what became known as the New Deal Coalition:

Urban working-class voters

African Americans (a historic shift from the Republican Party)

Southern whites

Catholics and Jews

Farmers and rural poor

Labor unions and progressives

This coalition would dominate American politics through the 1960s, setting the stage for civil rights, labor power, and federal economic management.

Cultural and Physical Transformation

The New Deal wasn’t just legislation—it was visible in the landscape.

In 1936 alone, WPA workers:

Built or repaired nearly 2,500 schools

Paved over 200,000 miles of roads

Constructed hundreds of airports, hospitals, and courthouses

Hired thousands of artists, writers, and musicians

New Deal murals adorned post offices. Theater groups performed Shakespeare and contemporary plays in public parks. Photographers captured the faces of hardship and resilience.

This blend of economic and cultural investment created a new sense of national identity—one where government, community, and creativity were intertwined.

The Dust Bowl’s Grip Continues

The Great Plains remained in crisis in 1936. That summer was one of the hottest on record, with temperatures in Kansas and Oklahoma exceeding 110°F. Crops failed again. Livestock died. Dust storms remained common.

The Soil Conservation Service continued promoting new techniques—crop rotation, contour plowing, shelterbelts—to reverse environmental degradation. The Resettlement Administration relocated families from unsustainable farms.

Though the worst of the Dust Bowl would pass by 1937, its trauma lingered in the soil and the psyche.

Labor Strengthens, and So Do Tensions

Labor unions gained ground thanks to the Wagner Act (1935) and the legitimacy conferred by federal support.

In 1936:

The United Auto Workers (UAW) began organizing General Motors plants.

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), newly formed, broke from the American Federation of Labor to organize unskilled industrial workers.

Sit-down strikes began to appear, especially in the auto and rubber industries.

These actions would crescendo into major labor showdowns in 1937, but 1936 marked the beginning of modern labor’s rise as a political and economic force.

Signs of Strain

Despite the year’s triumphs, Roosevelt and the New Deal faced increasing opposition:

Big business and the American Liberty League warned of creeping socialism.

Conservatives began mobilizing around concerns about spending, deficits, and federal overreach.

Some liberals and socialists complained the New Deal didn’t go far enough, particularly in addressing racial injustice, housing discrimination, and poverty among sharecroppers.

The Supreme Court also struck down key New Deal laws like the AAA and parts of the NIRA, setting up a constitutional clash that would come to a head in 1937.

Public Confidence Restored

Perhaps the most important achievement of 1936 was psychological.

The country had suffered for years under despair and distrust. By the end of 1936:

Banking was stable

Relief was widely available

People had jobs, even if temporary

The federal government was seen as a partner, not just a power

Dr. Markov concludes:

“1936 wasn’t the end of the Depression. But it was the end of fatalism. Americans once again believed they had a government that saw them—and stood with them.”

1936 – A Turning Point in American Democracy

The year 1936 confirmed that the Great Depression was not just an economic event—it was a redefinition of American governance. Through elections, public works, labor reform, and cultural renewal, Roosevelt reshaped what democracy meant during crisis.

The Depression was not over. But the Roosevelt landslide, the growth of the New Deal coalition, and the expanding reach of federal programs meant that the response to crisis would now be collective, enduring, and institutional.

From here, the battles ahead would be about how far the New Deal would go—not whether it should exist at all.