1938 - Recovery Resumes Amid Global Tensions and Domestic Reckoning

The year 1938 unfolded as a crucial period of partial economic recovery, political recalibration, and rising global instability. In the United States, the Roosevelt administration worked to reverse the damaging effects of the 1937 recession—often called the "Roosevelt Recession"—through renewed government spending and legislative adjustment. Abroad, totalitarian regimes escalated their aggression, bringing the world dangerously close to war. From the factory floor to the halls of Congress to the streets of Vienna, 1938 reflected a world caught between the lingering shadows of the Great Depression and the approaching storm of global conflict.

I. The Economic Landscape: Reversing the 1937 Recession

After the economic downturn of 1937, 1938 marked a shift back toward government intervention. Faced with rising unemployment—back up to nearly 20%—and a sharp contraction in industrial output, the Roosevelt administration moved to revive the New Deal’s momentum.

In April 1938, FDR signed the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, which authorized $3 billion in new government spending. Funds flowed into the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Public Works Administration (PWA), and other agencies to resume job creation and infrastructure development. These programs provided millions of Americans with employment and stabilized regional economies, from building roads to supporting cultural and educational institutions.

Industrial production began to recover by the third quarter of the year, and stock markets stabilized. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, signed in June, also set a national minimum wage and capped the workweek at 44 hours—a major labor milestone.

“1938 was a sobering course correction,” said Dr. Henry Waldron, economist and historian at Defined Benefits. “It became clear that fiscal and monetary restraint in 1937 had nearly undone years of recovery. Reinvestment was the only path forward.”

II. Legislative Shifts: Labor, Business, and Reform

The passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) not only improved working conditions but also reinforced the government’s long-term commitment to labor protections. While business leaders largely opposed it, citing cost concerns, the law laid the foundation for future worker rights and institutionalized the federal role in labor standards.

Yet, Roosevelt's political influence remained diminished following the failed 1937 court-packing plan. Even within the Democratic Party, a conservative bloc—later known as the "conservative coalition"—began pushing back against New Deal expansion. Roosevelt’s attempt to “purge” Democrats who opposed his reforms in the 1938 midterms largely failed, leading to significant Republican gains and signaling a legislative slowdown for the New Deal.

“The 1938 midterms were Roosevelt’s wake-up call,” said Dr. Waldron. “His vision remained popular, but his overreach made even allies cautious. The result was a more gridlocked, post-reform Congress.”

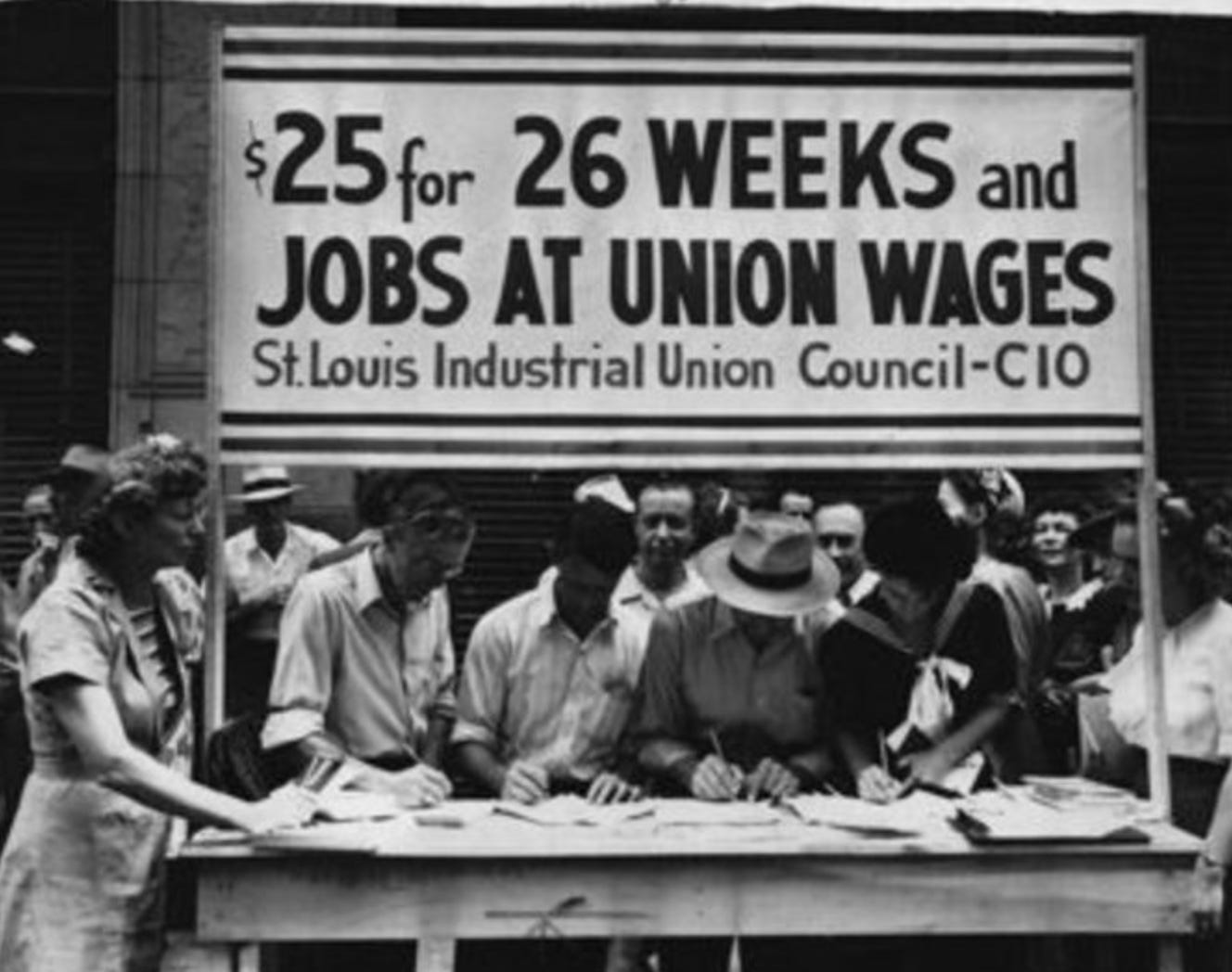

III. Labor Struggles and Union Movements

The labor movement, galvanized by earlier successes in the decade, saw growing tensions in 1938. The split between the AFL and CIO widened as both organizations competed for workers in emerging industries like steel, textiles, and rubber. Union membership continued to grow, but internal divisions and employer resistance made organizing difficult.

Strikes were frequent but less coordinated than in prior years. One notable example was the Remington Rand strike, where company tactics—known as the “Mohawk Valley formula”—were used to break labor resistance through propaganda and law enforcement cooperation.

Still, government intervention and public sentiment increasingly leaned toward protecting workers’ rights, setting the stage for stronger unionization in the 1940s.

IV. Foreign Affairs: A World Tilting Toward War

While 1938 brought some economic hope domestically, the global outlook darkened rapidly. Most alarmingly:

Germany annexed Austria in March in the Anschluss, a bloodless coup backed by Hitler’s propaganda and political maneuvering.

Later in September, the Munich Agreement allowed Hitler to annex the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, a policy of appeasement led by Britain and France in hopes of averting a broader war.

Kristallnacht in November 1938 marked a terrifying escalation of anti-Jewish violence in Nazi Germany, as Jewish homes, synagogues, and businesses were destroyed across the Reich.

American isolationism remained strong, but Roosevelt’s administration began preparing for the possibility of involvement. Congress passed legislation allowing military buildup, and the president made increasingly forceful statements warning of the threats posed by fascist regimes.

V. Culture and Society in 1938

Even in a tense economic and political climate, culture remained vibrant and politically aware. American literature and film of 1938 reflected the anxieties and hopes of a country still recovering.

Literature:

Pearl S. Buck won the Pulitzer Prize for The Good Earth, a novel of rural Chinese struggle with deep resonance for American readers facing hardship.

Rebecca West published The Thinking Reed, exploring the complex roles of women in a changing society.

Film:

You Can’t Take It With You, directed by Frank Capra, was a box office success and won the Academy Award for Best Picture—its themes of anti-corporate idealism and individualism resonated widely.

Bringing Up Baby (1938) and The Adventures of Robin Hood gave American audiences some much-needed escapist charm.

Music:

Big Band and Swing continued to dominate, with artists like Benny Goodman and Count Basie offering a rhythmic distraction from economic anxiety.

VI. Race, Civil Rights, and Inequality

Racial inequality remained severe in 1938. Despite some New Deal efforts reaching Black communities—especially through the WPA and CCC—segregation and discrimination in hiring, housing, and public works persisted. Southern legislators often blocked efforts to ensure equitable access to federal programs.

Nevertheless, Black leaders like Mary McLeod Bethune—an advisor to the Roosevelt administration—continued to push for greater inclusion. The National Negro Congress and labor unions also began advocating more forcefully for civil rights within the broader labor movement.

The Mexican Repatriation program, though it peaked earlier in the decade, still affected Latino families, many of whom remained displaced or economically marginalized in 1938.

VII. The Defined Benefits Perspective: Caution and Continuity

From a macroeconomic standpoint, 1938 was a year of lessons learned and systems rebalanced. It clarified that government support had to be sustained, not episodic. For pension systems, labor protection, and wage guarantees, the FLSA and other reforms laid foundations that would endure for generations.

According to Dr. Waldron of Defined Benefits, “1938 marked a return to cautious optimism, but it was tempered by hard-won wisdom. The Depression was still with us—but now we had a map out.”

Conclusion

1938 was a year of recalibration. In the U.S., renewed public investment helped stop the economic freefall of 1937. Legislation like the Fair Labor Standards Act demonstrated that reform could still progress, even if slowly. Globally, it became clear that the Depression’s social fallout—fascism, war, and displacement—was intensifying.

Though the New Deal lost some political momentum, its institutional legacy deepened. Unemployment remained high, but Americans had a stronger safety net and clearer expectations of government responsibility. Meanwhile, the international order frayed with each diplomatic failure and act of aggression abroad.

1938 was not the end of the Great Depression—but it was the year America stopped its backslide and began preparing, both economically and morally, for what would come next.