1941 - America Enters the War and Leaves the Depression Behind

The year 1941 was a watershed moment in U.S. history—a year that closed the curtain on the Great Depression and opened a new era of total war, global leadership, and economic transformation. After over a decade of economic hardship, America's reluctant path toward World War II ended on December 7, 1941, when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor. That single event not only thrust the United States into global conflict but also solidified the full mobilization of its economy, society, and political institutions. By the end of 1941, the Depression was no longer the central crisis facing Americans. War was.

I. Economic Revival Becomes Wartime Boom

Even before Pearl Harbor, 1941 saw a dramatic surge in industrial output and employment, driven by military demand. Factories expanded operations, steel production hit record levels, and shipyards hired tens of thousands. The Lend-Lease Act, passed in March, authorized the U.S. to supply arms and materials to Allied nations, most notably Britain and later the Soviet Union. This effectively turned America into the “arsenal of democracy,” a phrase coined by President Roosevelt in a radio address in December 1940 and put into practice throughout 1941.

Industrial production increased by nearly 30% in 1941 alone. Unemployment, which had stood at around 15% in 1940, fell below 10% for the first time since the 1920s. By year’s end, it was nearing 6%.

“The transformation in 1941 was stunning,” said Dr. Henry Waldron, economist and historian at Defined Benefits. “The Depression didn’t just end—it was eclipsed. War production reshaped the entire economy faster than any domestic policy ever could.”

II. Pearl Harbor Changes Everything

The pivotal moment of 1941 occurred on December 7, when Japan launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Over 2,400 Americans were killed, and much of the Pacific Fleet was damaged or destroyed. The next day, Congress declared war on Japan; within days, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

This event transformed public opinion overnight. While many Americans had favored neutrality or limited aid to the Allies, Pearl Harbor galvanized national unity. Isolationism collapsed, and patriotic fervor spread rapidly across the country. Millions volunteered for military service, and recruitment centers saw long lines.

III. Mobilizing for Total War

Following the attack, the federal government initiated an unprecedented mobilization effort. Roosevelt established the War Production Board to coordinate factory conversions and resource allocation. The Selective Service System expanded dramatically, and the draft age was lowered.

The government also began rationing key resources, including gasoline, rubber, and food staples, in anticipation of shortages. War bonds were promoted aggressively to help finance the conflict, and new taxes were introduced to support the war budget.

The auto industry stopped producing civilian vehicles by year’s end and began transitioning to tanks, planes, and military trucks. The Liberty ship program ramped up, with shipyards producing one cargo vessel every few days by 1942.

IV. Women and Minorities Enter the Workforce

As millions of men entered the military, labor shortages became acute. In response, women were recruited into factories, shipyards, and government offices in record numbers. Though the iconic image of “Rosie the Riveter” would not fully take hold until 1942, 1941 was the year when women’s presence in heavy industry began to grow significantly.

Meanwhile, African Americans, Latino workers, and other marginalized groups also began to enter previously segregated industries. Civil rights leaders like A. Philip Randolph pressured the federal government to address discrimination in defense employment.

These efforts led to Executive Order 8802, signed by Roosevelt in June 1941, which prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC)—a landmark step toward workplace civil rights.

“8802 wasn’t just about labor rights,” said Mr. Waldron. “It was a recognition that democracy at home had to mean something, especially when fighting fascism abroad.”

V. Foreign Policy and the Road to War

Prior to Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt had already moved the U.S. closer to active involvement in World War II. The Lend-Lease Act allowed the U.S. to ship over $1 billion in aid to Britain, China, and later the USSR. U.S. naval convoys began escorting Allied shipping in the Atlantic, and by fall 1941, American and German ships had already exchanged fire.

In August, Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met off the coast of Newfoundland to issue the Atlantic Charter, a joint declaration of war aims and postwar visions. It outlined principles such as self-determination, free trade, and disarmament—setting the ideological stage for U.S. entry into the war.

VI. Arts and Culture: A Shift in Mood

Culture in 1941 reflected the growing sense of urgency and purpose. Films like Sergeant York, Citizen Kane, and The Maltese Falcon dominated theaters. Radio broadcasts and newsreels focused increasingly on European battlefields, Axis aggression, and the threat to democracy.

Comic books also gained popularity—Captain America debuted in March 1941, famously punching Hitler on the cover months before Pearl Harbor. The character became an early symbol of wartime patriotism and resistance.

Popular music, meanwhile, ranged from sentimental ballads like “The White Cliffs of Dover” to swing hits that filled dance halls and bolstered morale. Big band music reached its peak in 1941, with artists like Glenn Miller and Benny Goodman becoming national icons.

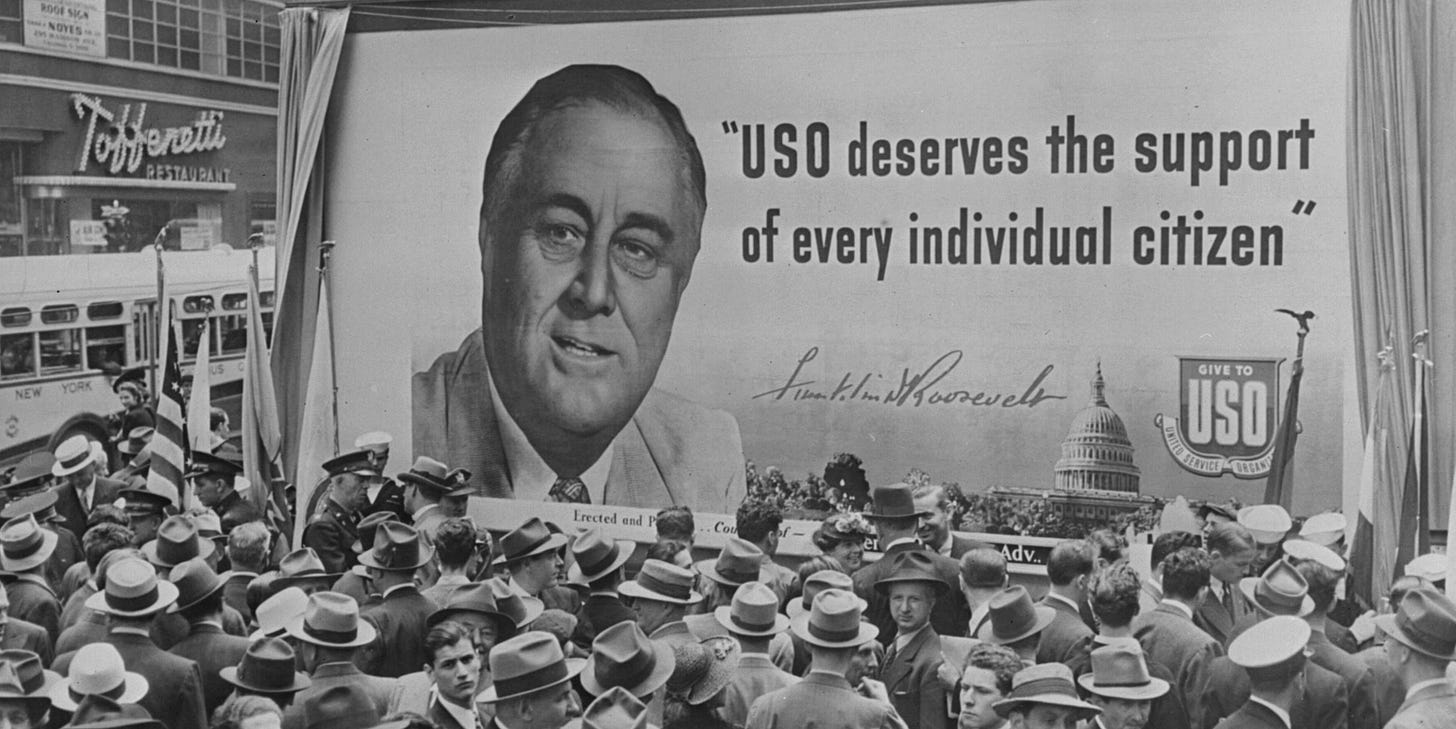

VII. The American Homefront: Unity and Sacrifice

In 1941, a new kind of American unity emerged—not based on economic relief, but on national defense. The civilian population was called on to ration, save, work, and serve. Victory gardens, scrap metal drives, and bond campaigns became commonplace.

The Depression-era habits of thrift and resourcefulness now aligned with national goals. People who had spent the 1930s conserving out of necessity were now conserving out of duty.

This transformation created a new sense of national purpose that differed dramatically from the despair and fragmentation of the 1930s. By December 1941, America was no longer a nation in crisis—it was a nation at war.

The Year the World Changed

1941 was the hinge year between two American eras. It ended the Great Depression not with a policy or a program, but with a mobilization that reshaped every part of American life. The war effort unleashed industrial might, redefined the workforce, and elevated the U.S. into a central global role.

The trauma of Pearl Harbor erased doubts about America's direction. The sacrifices of the 1930s were now repurposed for national strength. What began as a year of uneasy peace ended with the nation unified and prepared for a long, total war.

In the words of Mr. Waldron, “By the end of 1941, the question was no longer whether the Depression was over. The question was how the greatest democracy in history would rise to meet the greatest threat it had ever faced.”