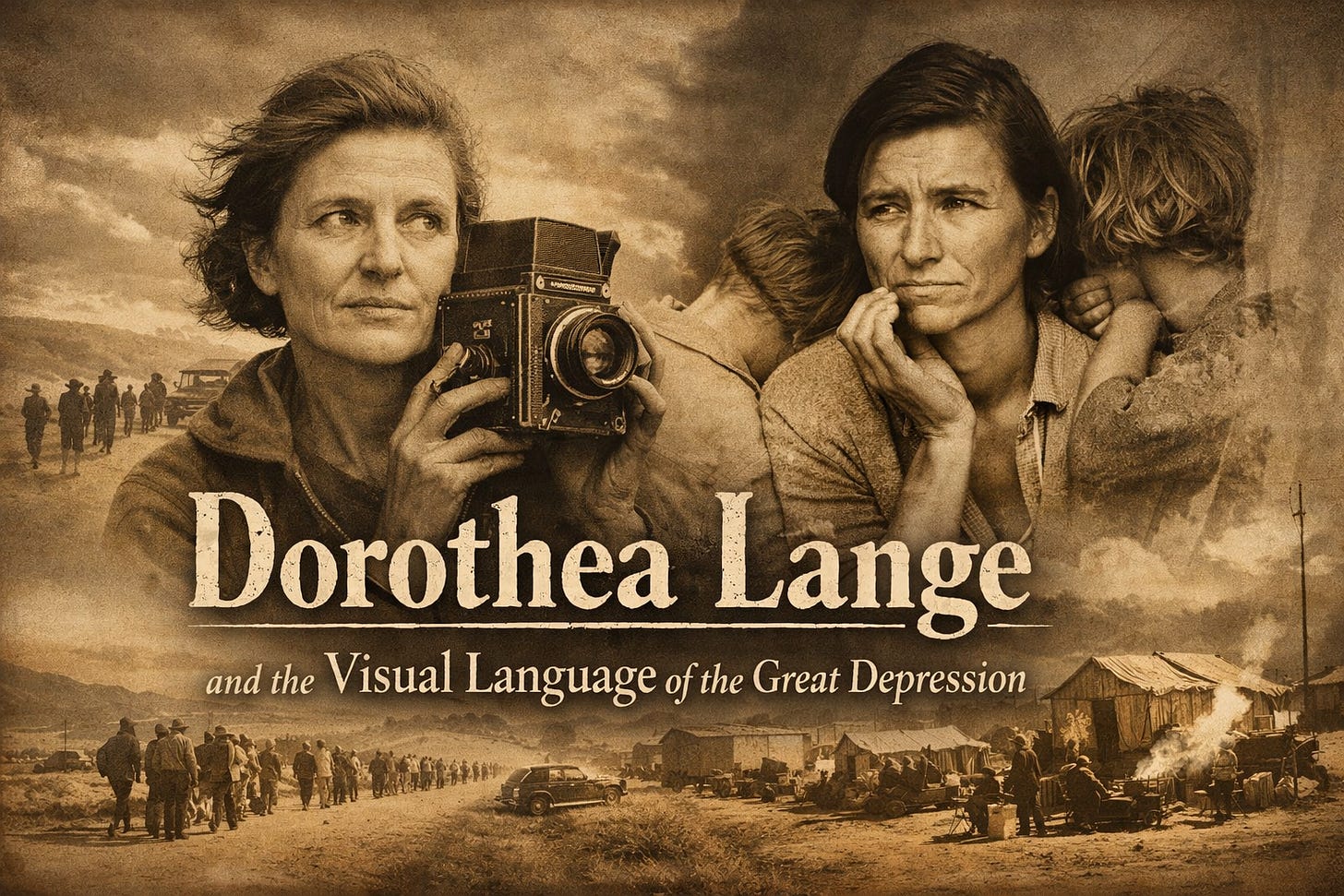

Dorothea Lange and the Visual Language of the Great Depression

Dorothea Lange stands as one of the most influential documentary photographers in American history not simply because she recorded the Great Depression, but because she reshaped how Americans understood it. Her photographs translated economic collapse into moral urgency, transforming abstract hardship into intimate human experience. In doing so, Lange demonstrated that images could function as political instruments as powerful as legislation. Her work reveals how visual culture helped legitimize federal intervention during a moment of national crisis.¹

Born in 1895 in Hoboken, New Jersey, Lange’s early life was marked by instability and illness. Contracting polio as a child left her with a permanent limp, shaping her awareness of vulnerability and exclusion.² This experience fostered a lifelong sensitivity to marginalization and suffering. Rather than distancing herself from hardship, Lange gravitated toward it with empathy and attentiveness.

Lange trained as a portrait photographer in New York before relocating to San Francisco, where she established a successful commercial studio. Photographing affluent clients refined her technical precision and compositional discipline.³ These skills later distinguished her documentary work from more casual or sensational images of poverty. Her background ensured that her photographs conveyed seriousness rather than spectacle.

The onset of the Great Depression marked a decisive shift in Lange’s career. As unemployment and homelessness became visible outside her studio, she felt compelled to redirect her lens toward the streets.⁴ Breadlines and jobless men replaced elite interiors as her primary subjects. This transition reflected not only economic change, but an evolving ethical commitment.

Lange viewed photography as a form of responsibility rather than neutral observation. She believed that seeing suffering imposed an obligation on the viewer.⁵ Photography, in her view, could confront society with realities it preferred to ignore. This belief anchored her work in moral purpose rather than artistic detachment.

In 1935, Lange was hired by the federal Resettlement Administration, later renamed the Farm Security Administration (FSA). The agency sought visual evidence to support New Deal relief programs and build public legitimacy.⁶ Lange’s assignment was not merely descriptive but persuasive. Her images translated policy goals into human terms.

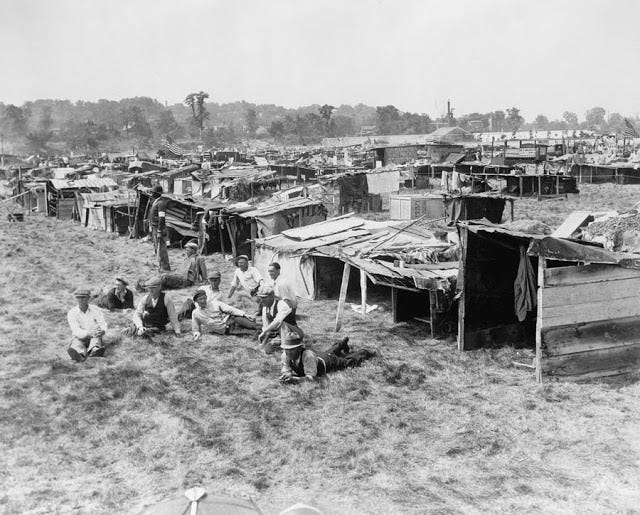

Through the FSA, Lange traveled extensively across California and the American West. She documented migrant camps, roadside settlements, and families displaced by drought, foreclosure, and agricultural mechanization.⁷ These journeys revealed the structural forces behind mass displacement. Her photographs emphasized systemic failure rather than individual fault.

Lange’s method relied on engagement rather than distance. She spoke with her subjects, listened to their stories, and photographed them with dignity.⁸ This approach resisted sensationalism and pity. Instead, her images emphasized endurance, restraint, and quiet resolve.

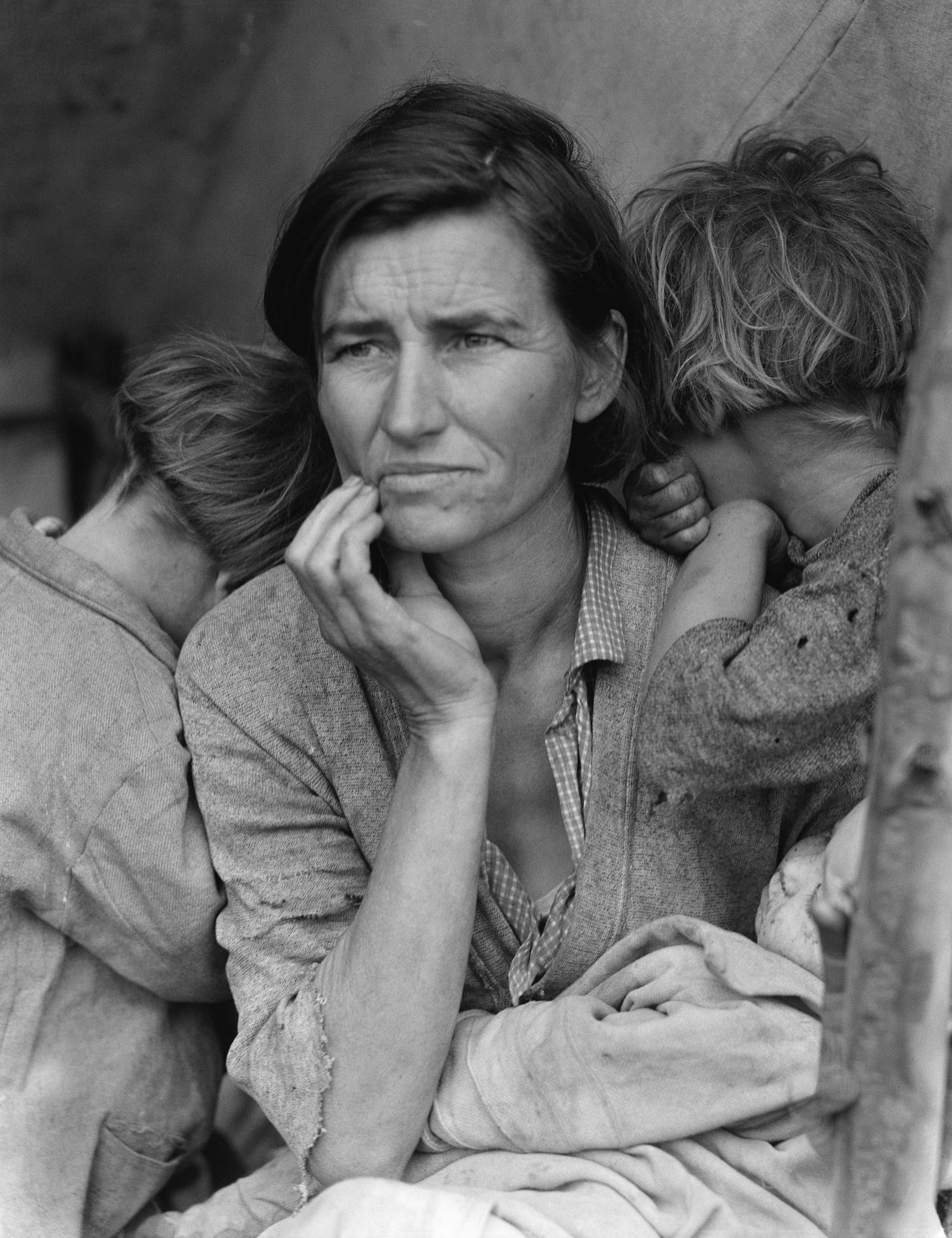

Her most famous photograph, Migrant Mother (1936), became the defining image of the Great Depression. The photograph depicts Florence Owens Thompson surrounded by her children, her gaze fixed beyond the frame.⁹ The expression conveys anxiety, strength, and uncertainty simultaneously. This emotional complexity explains the photograph’s enduring power.

Migrant Mother did more than document hardship—it defined it visually. For millions of Americans, the image became the face of Depression-era poverty.¹⁰ It condensed national trauma into a single human expression. Through this image, Lange shaped collective memory.

Importantly, Lange’s intent was practical rather than symbolic. She photographed the scene to document urgent need. Shortly after publication, emergency food aid was sent to the camp.¹¹ This outcome demonstrated photography’s capacity to produce immediate political action.

Lange’s work challenged dominant stereotypes about poverty. She rejected narratives that portrayed the poor as lazy or morally deficient.¹² Instead, her photographs emphasized structural forces such as environmental disaster and economic collapse. This framing aligned with New Deal arguments for federal responsibility.

At the same time, Lange’s work raises ethical questions. Florence Thompson later expressed discomfort with the fame of Migrant Mother and her lack of control over the image.¹³ This tension highlights the limits of documentary photography. Iconic images can mobilize empathy while simplifying complex realities.

Lange’s concern with displacement extended beyond the Depression. During World War II, she documented the forced internment of Japanese Americans. Her photographs captured loss, confinement, and the erosion of civil liberties.¹⁴ Many were censored for decades due to their critical portrayal of government policy.

Across historical contexts, Lange focused on how institutions shape suffering. Whether documenting migrant laborers or incarcerated citizens, she emphasized systemic responsibility.¹⁵ Her work questioned the neutrality of state power. Photography became a means of accountability.

Stylistically, Lange favored tight framing and minimal background detail. Faces, hands, and posture became central elements of her visual language.¹⁶ This emphasis heightened emotional engagement without stripping subjects of agency. Her restraint strengthened her images’ authority.

Lange’s influence extended well beyond the 1930s. She helped establish documentary photography as a tool of social critique rather than passive observation.¹⁷ Later photojournalists adopted her emphasis on empathy and ethics. Her work set enduring standards for visual storytelling.

She also shaped how Americans interpret images. Lange taught viewers to read emotion, context, and power relations within a single frame.¹⁸ This visual literacy encouraged deeper civic engagement. Photography became a means of understanding, not just seeing.

Later in life, Lange rejected the idea of photographic neutrality. She argued that choosing where to point the camera is itself a moral act.¹⁹ This philosophy underscored her belief in responsibility over detachment. Her work exemplified engaged witnessing.

Dorothea Lange’s legacy lies in her ability to humanize history. Through images like Migrant Mother, she gave the Great Depression a face that demanded response. Her photography reveals that during moments of crisis, legitimacy depends not only on policy but on perception.²⁰ In showing how images can shape conscience, Lange permanently altered American social and political consciousness.

Notes

William Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), 87.

Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 9.

Gordon, Dorothea Lange, 15.

Dorothea Lange and Paul Schuster Taylor, An American Exodus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1939), 18.

Stott, Documentary Expression, 92.

Library of Congress, “Dorothea Lange Collection,” accessed [date].

Gordon, Dorothea Lange, 41.

Lange and Taylor, An American Exodus, 23.

Library of Congress, “Migrant Mother,” accessed [date].

Stott, Documentary Expression, 101.

Gordon, Dorothea Lange, 45.

Stott, Documentary Expression, 98.

Gordon, Dorothea Lange, 52.

Library of Congress, “Japanese American Internment Photographs,” accessed [date].

Stott, Documentary Expression, 110.

Gordon, Dorothea Lange, 60.

Stott, Documentary Expression, 115.

Lange and Taylor, An American Exodus, 29.

Lange and Taylor, An American Exodus, 31.

Stott, Documentary Expression, 121.

Bibliography

Gordon, Linda. Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits. New York: W. W. Norton, 2009.

Lange, Dorothea, and Paul Schuster Taylor. An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1939.

Library of Congress. Dorothea Lange Collection. https://www.loc.gov/collections/dorothea-lange/.

Stott, William. Documentary Expression and Thirties America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.