Feeding the Hungry, Buying Silence: Al Capone, Power, and Public Sympathy in the Great Depression

Al Capone is often remembered as the most notorious criminal figure of the early twentieth century, but his rise and fall cannot be understood without reference to the broader social and economic upheaval of the Great Depression. Although Capone reached the height of his power just before the Depression began, the economic collapse that followed reshaped both his public image and the government’s determination to bring him down. More than a story of crime, Capone’s experience during the Depression reveals how economic crisis can blur moral boundaries, elevate private power in the absence of public relief, and ultimately provoke a forceful reassertion of state authority.

Capone’s ascent was rooted in the era of Prohibition, when the illegal production and distribution of alcohol created enormous profit opportunities for criminal syndicates. Operating primarily through the Chicago Outfit, Capone built a vast empire encompassing bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution. By the late 1920s, his organization generated tens of millions of dollars annually, allowing him to bribe officials, intimidate rivals, and exert effective control over large parts of Chicago’s underworld. To many Americans before 1929, Capone symbolized the excesses and contradictions of the Roaring Twenties—a period of visible prosperity for some, paired with deep corruption and lawlessness beneath the surface.

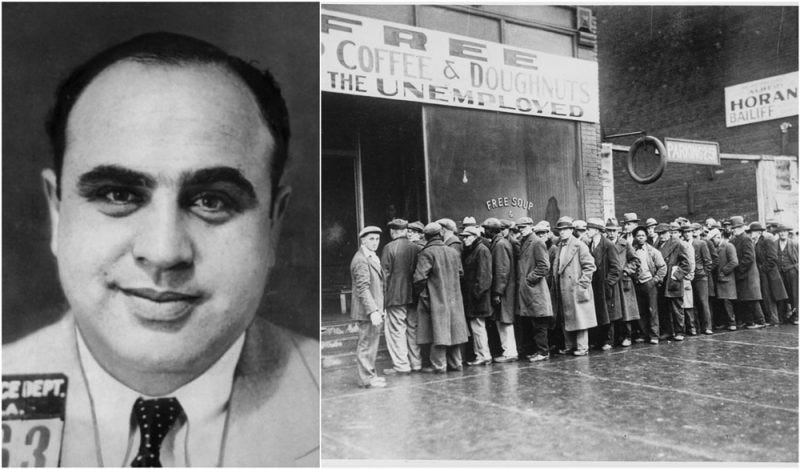

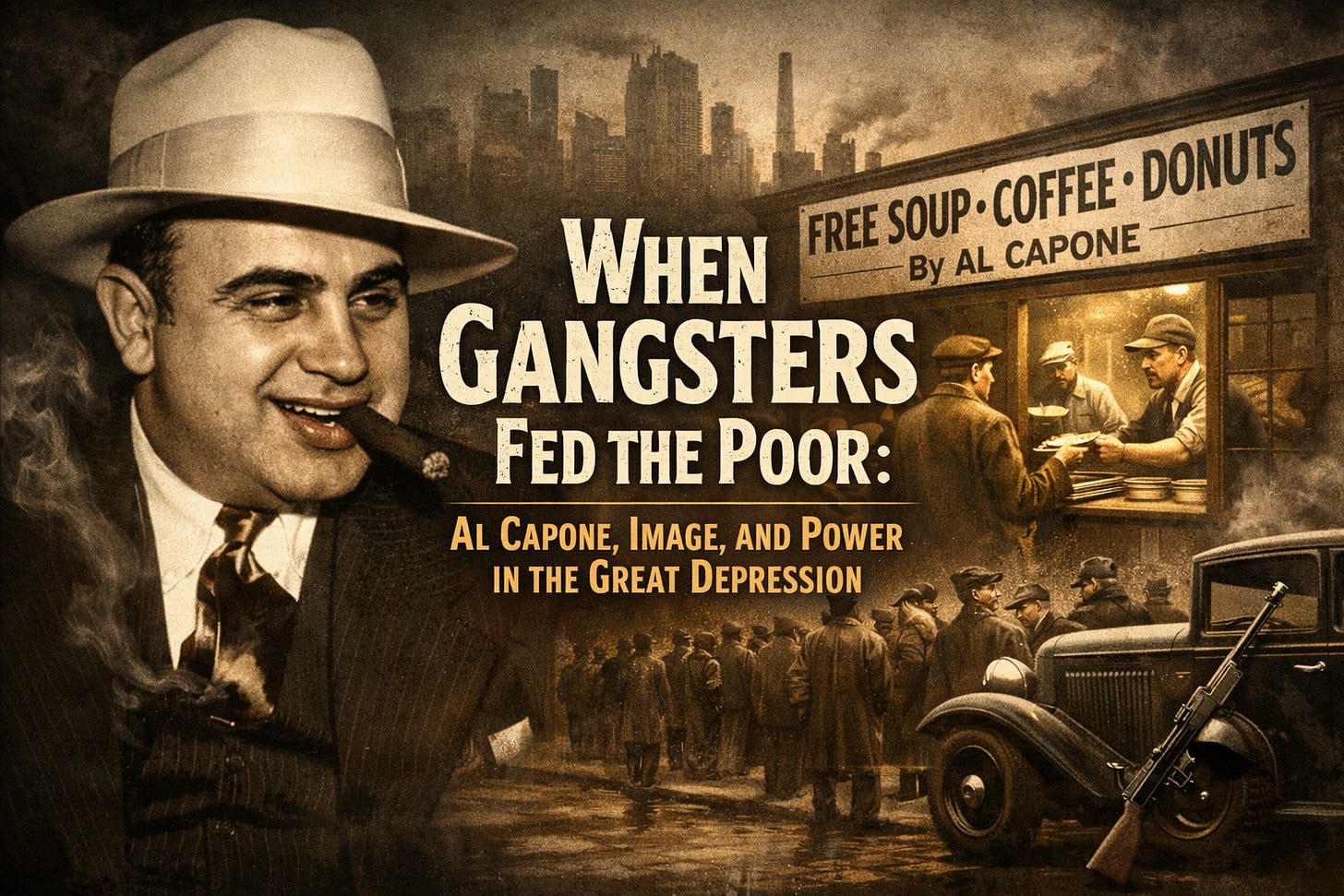

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 dramatically altered this context. As unemployment surged and banks collapsed, municipal relief systems proved inadequate and slow-moving. In this vacuum, Capone pursued a calculated effort to recast himself as a public benefactor. In November 1930, his organization opened a highly publicized soup kitchen on Chicago’s South Side, serving thousands of meals per day—typically soup, bread, and coffee—to unemployed men. The operation was orderly, efficient, and deliberately visible. While the cost was negligible relative to Capone’s criminal profits, the public-relations value was immense. Newspapers widely covered the kitchens, often emphasizing the irony that a criminal organization was feeding the hungry while public institutions struggled to respond.

These soup kitchens were not acts of spontaneous generosity but an early form of image management—an effort to secure legitimacy through social welfare in an era before a robust federal safety net. Capone himself avoided serving food publicly, yet his name was carefully linked to the effort, reinforcing a narrative of the gangster as a provider. For many desperate Chicagoans, the immediate reality of a hot meal outweighed concerns about its source. As one contemporary observer paraphrased in the press, the most efficient relief operation in the city appeared to be run by a man the government could not yet jail. This uneasy admiration reflected the broader moral ambiguity of the Depression years.

However, reformers and law-enforcement officials were far less sympathetic. They viewed the soup kitchens as cynical manipulation rather than genuine charity, and as evidence of how criminal wealth could distort civic life. Moreover, as the Depression deepened, tolerance for inequality diminished. Capone’s conspicuous lifestyle—luxury suits, armored cars, and lavish homes—stood in stark contrast to the suffering of ordinary Americans. What once seemed glamorous increasingly appeared obscene, especially when paired with the knowledge that his income went untaxed.

This shift in public sentiment coincided with a change in enforcement strategy. Unable to secure convictions for violent crimes amid bribery and intimidation, federal authorities turned to financial accountability. In a Depression-era climate increasingly focused on fairness, the idea that a man could earn millions while contributing nothing to public coffers became politically indefensible. Capone’s philanthropy, rather than shielding him, underscored this contradiction and strengthened the resolve to prosecute him for tax evasion.

Capone’s 1931 conviction marked a decisive turning point. Sentenced to prison at the height of the Depression, he became a symbol not of daring rebellion but of excess punished. His downfall demonstrated the expanding reach of the federal government and foreshadowed the broader consolidation of authority that would characterize the New Deal era. Organized crime figures were no longer romanticized as folk heroes exploiting loopholes in a flawed system, but increasingly condemned as predators thriving at society’s expense.

In retrospect, Al Capone’s relationship to the Great Depression is one of contrast and consequence. His empire was built in an era of lax enforcement and institutional weakness, but it collapsed during a period demanding reform, accountability, and public responsibility. The Depression did not create Capone, but it reshaped how Americans viewed him and accelerated his fall. His story ultimately serves as a lens through which to understand how economic catastrophe can redefine legitimacy, expose the limits of private power, and strengthen the resolve of institutions to restore social order.