Power on the Airwaves: Father Coughlin and the Lure of Mass Power

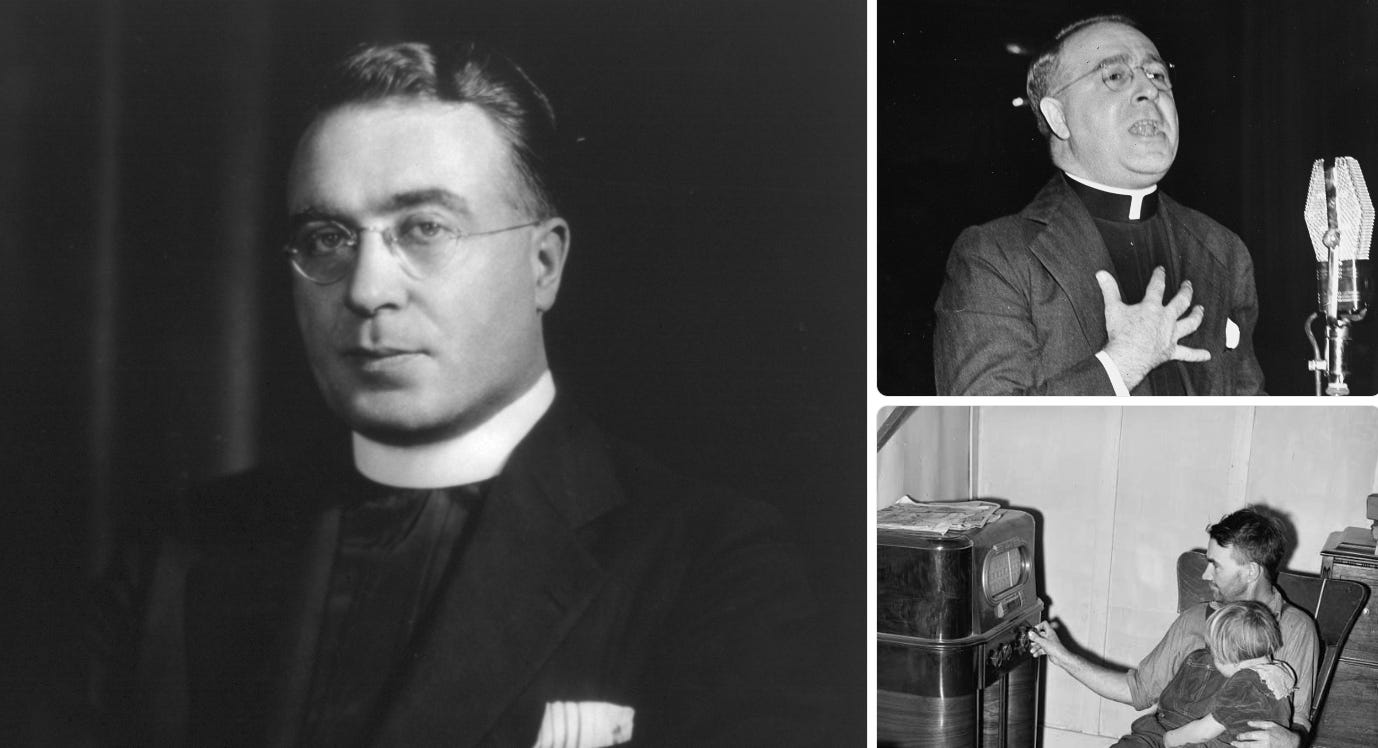

Father Charles Coughlin emerged as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the Great Depression. As a Catholic priest with a national radio audience, he reached millions of Americans at a time of deep economic fear. His sermons blended religious language with political and economic commentary. For many listeners, he became a voice of certainty during chaos.

The Great Depression created fertile ground for Coughlin’s rise. Mass unemployment, bank failures, and widespread poverty undermined trust in traditional institutions. Americans searched for explanations and solutions that felt immediate and moral. Coughlin offered both, framed through religious authority.

Initially, Coughlin positioned himself as a defender of the common man. He criticized unregulated capitalism and the power of large banks. His early rhetoric emphasized social justice, economic reform, and relief for the poor. This message resonated strongly with struggling working-class listeners.

Coughlin strongly supported Franklin D. Roosevelt during the early New Deal years. He viewed Roosevelt’s policies as a necessary correction to financial excess. Over the radio, he praised government intervention and monetary reform. His endorsement helped legitimize New Deal ideas among religious and populist audiences.

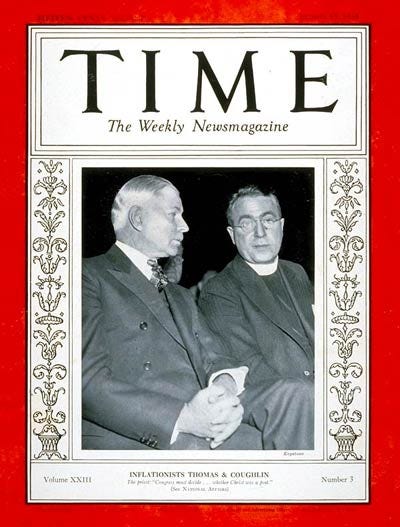

Central to Coughlin’s economic critique was his opposition to the gold standard. He argued that monetary scarcity deepened the Depression unnecessarily. Coughlin promoted inflationary policies and expanded credit as tools for recovery. These views aligned with broader populist economic movements of the era.

As the Depression dragged on, Coughlin’s tone shifted. Frustration with the pace and direction of reform hardened into anger. He began to portray economic suffering as the result of deliberate betrayal rather than structural complexity. This shift marked a turning point in his public role.

Coughlin broke decisively with Roosevelt by the mid-1930s. He accused the administration of serving financial elites instead of ordinary Americans. His broadcasts became increasingly hostile toward the New Deal. The rupture reflected broader fractures within Depression-era reform coalitions.

Religion played a key role in Coughlin’s appeal. He framed economic issues as moral battles between good and evil. Capitalism, banking, and government policy were presented in spiritual terms. This moral absolutism simplified complex economic realities for mass audiences.

Coughlin’s radio presence was unprecedented in scale. At his peak, his broadcasts reached an estimated 30 million listeners. Radio allowed him to bypass traditional political institutions entirely. The technology amplified both his influence and his volatility.

During the Depression, populism often blurred into scapegoating. Coughlin increasingly blamed unnamed conspirators for economic collapse. His rhetoric grew conspiratorial and exclusionary. This evolution revealed the darker potential of mass populist movements.

Antisemitism became a defining feature of Coughlin’s later Depression-era sermons. He falsely linked Jewish communities to international finance and communism. These claims exploited fear and resentment fueled by economic distress. They also aligned his movement with European authoritarian ideologies.

Coughlin’s newspaper, Social Justice, expanded his influence beyond radio. The publication repeated and intensified his economic and political messages. It circulated widely during the late Depression years. Print media allowed his ideas to persist even as radio stations pushed back.

The federal government and Catholic Church grew increasingly concerned. Officials worried that Coughlin’s rhetoric undermined social stability. Church leaders feared political entanglement and reputational damage. These tensions reflected the broader challenge of regulating speech during crisis.

The Depression forced Americans to confront the boundaries of free expression. Coughlin tested those boundaries aggressively. His popularity made censorship politically risky. Yet his influence raised questions about responsibility in mass communication.

Coughlin’s movement culminated in the formation of the National Union for Social Justice. The organization sought to translate radio populism into political power. Its limited success revealed the difficulty of sustaining movements built on personality alone. Still, it demonstrated the political energy unleashed by Depression-era anger.

As World War II approached, tolerance for Coughlin declined sharply. His isolationism and authoritarian sympathies alarmed both government and church authorities. The national mood shifted away from Depression populism toward wartime unity. His platform narrowed rapidly.

By the early 1940s, Coughlin was forced off the radio. Government pressure and church intervention curtailed his public voice. His fall was as dramatic as his rise. It marked the end of one of the Depression’s most volatile figures.

Coughlin’s relationship to the Great Depression is inseparable from mass fear and uncertainty. He thrived on economic despair but also shaped how that despair was interpreted. His sermons offered clarity at the cost of nuance. The tradeoff proved dangerous.

Historically, Coughlin illustrates how economic crises can radicalize public discourse. The Depression weakened trust in democratic processes and expertise. Charismatic figures filled the vacuum. Coughlin stands as a warning about moral authority fused with political rage.

His legacy complicates narratives of Depression-era reform. Alongside constructive New Deal policies existed destructive demagoguery. Both drew from the same well of suffering. The difference lay in whether hardship was met with solidarity or division.

Ultimately, Father Charles Coughlin represents the perilous edge of Depression-era populism. He translated genuine economic pain into grievance-driven politics. While he spoke to real suffering, his solutions eroded democratic norms. His story remains a cautionary chapter in the history of crisis and influence.