Saving Capitalism from Itself: John Maynard Keynes and the Great Depression

John Maynard Keynes occupies a central place in the history of the Great Depression not because he caused the crisis, but because he fundamentally transformed how governments understood and responded to it. Before Keynes, economic downturns were widely viewed as self-correcting. The unprecedented scale and persistence of the Depression undermined this belief. Keynes offered a framework explaining why mass unemployment could endure—and why government intervention was necessary.¹

The Great Depression began with the stock market crash of 1929, but its severity revealed deeper structural weaknesses in global capitalism. Industrial production collapsed, banks failed, and unemployment soared across Europe and the United States. Traditional remedies failed to reverse the decline. These failures created fertile ground for Keynes’s ideas.²

Classical economics dominated policymaking before the 1930s. It assumed flexible wages and prices would restore equilibrium. Government intervention, particularly deficit spending, was viewed as dangerous. Balanced budgets were treated as both an economic and moral necessity.³

Keynes rejected this logic. He argued that during severe downturns, economies could become trapped in long-term stagnation. Firms would not invest due to pessimistic expectations, and consumers would reduce spending out of fear. This feedback loop prevented recovery.⁴

Central to Keynes’s argument was aggregate demand, or total spending in the economy. Keynes believed the Depression persisted because aggregate demand had collapsed. Without demand, businesses had no reason to hire or expand. Lower wages alone could not solve the problem.⁵

Keynes also challenged conventional views on saving. He identified the “paradox of thrift,” where increased individual saving during downturns reduces overall demand. What appeared prudent at the household level became destructive at the national level.⁶ This insight directly contradicted classical assumptions.

Early government responses emphasized austerity. In the United States, Herbert Hoover prioritized balanced budgets and voluntary relief. European governments adopted similar strategies. Keynes warned these policies deepened the Depression by withdrawing spending during collapse.⁷

Keynes proposed that governments act as spenders of last resort. When private investment falters, public spending must fill the gap. The goal was not efficiency but restoring demand and employment. Keynes famously argued that even wasteful spending was preferable to inaction.⁸

These ideas provoked controversy. Critics feared deficit spending would undermine fiscal discipline and confidence. Keynes countered that deficits during downturns were temporary and necessary. Budget balance, he argued, should be pursued over the economic cycle—not during crisis.⁹

Keynes’s influence appeared indirectly in U.S. policy. Franklin D. Roosevelt did not initially identify as a Keynesian, but New Deal policies aligned with Keynes’s thinking. Public works and relief spending sought to stimulate demand and employment.¹⁰

Programs like the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps injected income directly into the economy. These initiatives contradicted classical orthodoxy but reflected Keynes’s belief that employment itself was stimulus. The New Deal represented a partial shift toward Keynesian logic.¹¹

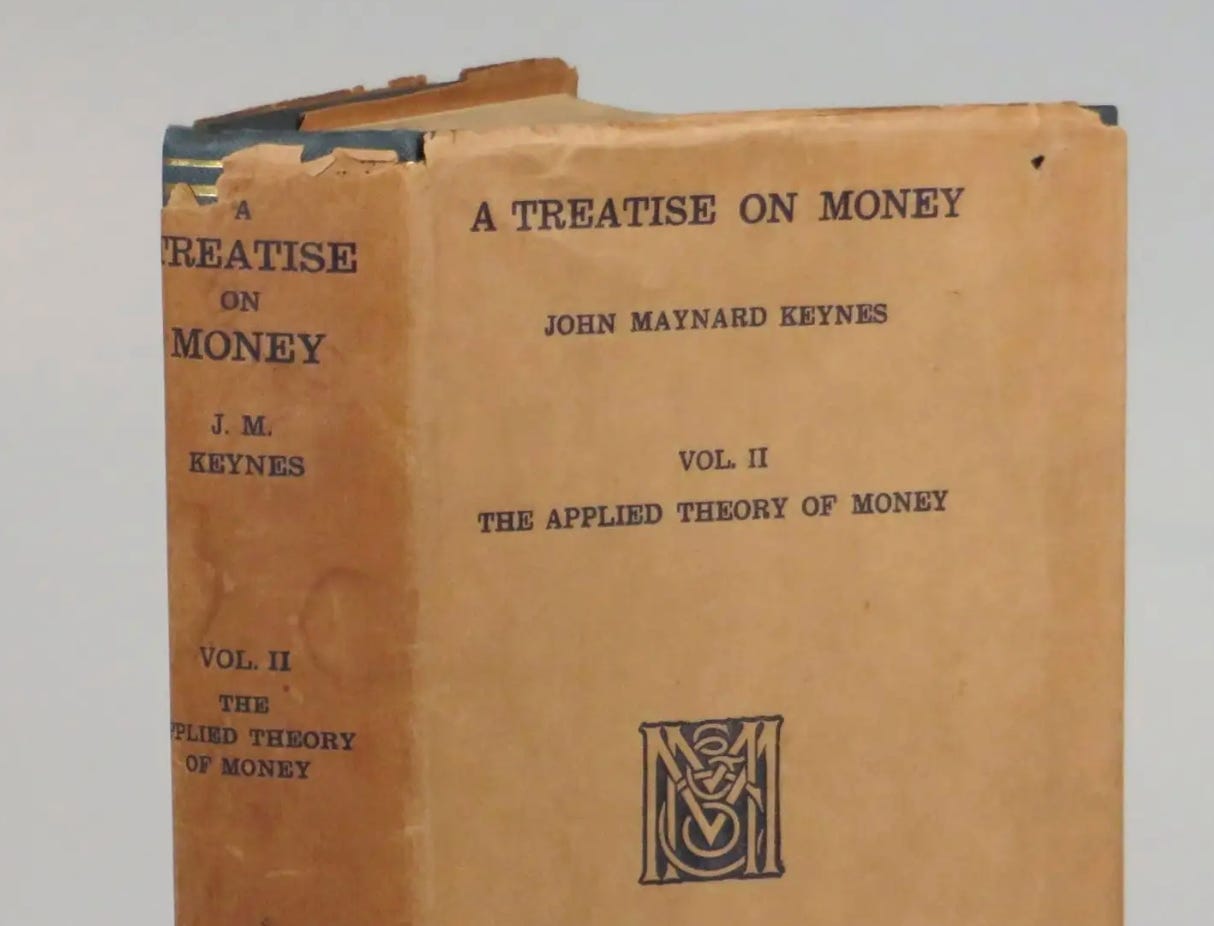

Keynes formalized his ideas in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). Written in response to the Depression, the book challenged the foundations of classical economics. It explained why unemployment could persist indefinitely without intervention.¹²

A radical element of The General Theory was its rejection of automatic full employment. Keynes emphasized uncertainty, expectations, and “animal spirits” as drivers of economic behavior. These psychological factors made markets unstable.¹³

Despite growing influence, Keynesian policy was not fully implemented during the Depression. It was World War II that provided definitive proof. Massive government spending eliminated unemployment almost overnight.¹⁴

After the war, Keynesian economics became dominant in Western governments. Full employment became a policy goal. Countercyclical fiscal policy was institutionalized. Keynes’s ideas shaped postwar economic management.¹⁵

Keynesianism reshaped the relationship between citizens and the state. Economic security became a public responsibility. Social insurance and welfare programs gained legitimacy through Keynesian reasoning.¹⁶

Critics later argued Keynesianism contributed to inflation and state overreach. Stagflation in the 1970s weakened its dominance. Yet its core insight—that markets can fail catastrophically—remained influential.¹⁷

Keynes’s relevance reemerged during later crises, including the 2008 financial collapse and the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments again rejected austerity in favor of stimulus. These responses echoed Depression-era Keynesian logic.¹⁸

Keynes’s connection to the Great Depression is both historical and intellectual. The crisis shaped his thinking, and his thinking reshaped global responses to crisis. He reoriented economics toward immediate human consequences.¹⁹

In retrospect, Keynes did not merely interpret the Great Depression—he changed its meaning. He demonstrated that mass unemployment was neither inevitable nor acceptable. His legacy endures whenever governments act decisively during economic collapse.²⁰

“What Keynes understood during the Great Depression is something we still grapple with today,” says Robert Mowry of Del Mar Medical Pensions. “Markets don’t always self-correct on a human timetable. Keynes gave policymakers permission to prioritize stability, employment, and long-term security over short-term orthodoxy—an insight that still underpins modern retirement systems and risk-pooling structures.”

Notes

Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: The Economist as Savior (New York: Penguin, 1992), 3–5.

Barry Eichengreen, Golden Fetters (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 1–4.

John Kenneth Galbraith, The Great Crash, 1929 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1955), 186–188.

John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: Macmillan, 1936), 249.

Keynes, General Theory, 25–27.

Keynes, General Theory, 173–175.

Skidelsky, Economist as Savior, 121–124.

Keynes, General Theory, 129.

Skidelsky, Economist as Savior, 136.

William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (New York: Harper & Row, 1963), 35–38.

Leuchtenburg, New Deal, 61–64.

Keynes, General Theory, vii–ix.

Keynes, General Theory, 161–162.

Galbraith, The Great Crash, 203.

Skidelsky, Economist as Savior, 297–300.

Eichengreen, Golden Fetters, 387–390.

Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 78–80.

Paul Krugman, End This Depression Now! (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 15–18.

Skidelsky, Economist as Savior, 401.

Krugman, End This Depression Now!, 214.

Bibliography

Eichengreen, Barry. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Galbraith, John Kenneth. The Great Crash, 1929. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1955.

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Macmillan, 1936.

Krugman, Paul. End This Depression Now!. New York: W. W. Norton, 2012.

Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

Skidelsky, Robert. John Maynard Keynes: The Economist as Savior. New York: Penguin, 1992.