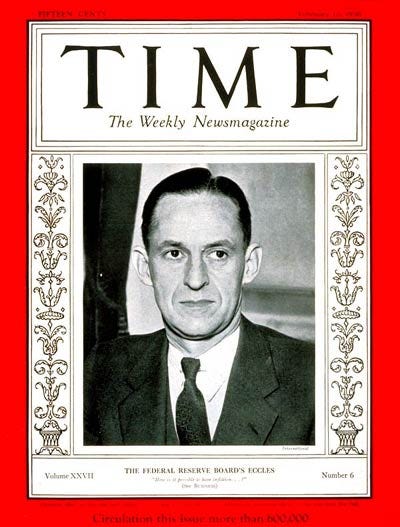

The Banker Who Learned to Spend: Marriner Eccles and the Reinvention of American Monetary Power

Few figures were more unlikely champions of government spending than Marriner Eccles. A wealthy Utah banker raised on fiscal restraint and business discipline, Eccles arrived in Washington during the Great Depression arguing that balanced budgets and tight money were not virtues but dangers. Markets, he believed, could fail catastrophically—and when they did, government had an obligation to act decisively. At a moment when austerity was treated as moral seriousness, Eccles advanced a radical proposition: public spending was not reckless, but necessary when private demand collapsed.

Eccles rose to national prominence as American economic thinking unraveled alongside its financial system. The Depression, in his view, was not the product of individual excess or temporary panic, but of deep structural imbalance. Wealth had become too concentrated, savings too idle, and consumption too weak to sustain growth. Without intervention, the economy would not self-correct—it would stagnate.

Why Orthodoxy Made the Depression Worse

When Eccles entered Washington in the early 1930s, policy was still governed by classical assumptions: limited government, tight credit, and faith in self-adjusting markets. Eccles rejected this framework outright. He argued that extreme inequality had drained purchasing power from the economy, leaving businesses without customers and workers without wages. Capital accumulated where it could not be productively deployed, while mass unemployment suppressed demand further.

In this diagnosis, the Depression was not cyclical but systemic. Waiting for markets to heal themselves was not prudence—it was paralysis. Recovery required deliberate, coordinated action to restore consumption and employment, even if that meant abandoning long-held fiscal dogma.

When Theory Entered the Federal Reserve

Although John Maynard Keynes was articulating similar ideas in Britain, Eccles arrived at his conclusions independently and brought them directly into the machinery of American government. As chair of the Federal Reserve, he advocated deficit-financed public spending, progressive taxation, and countercyclical fiscal policy. These were not emergency measures in his mind, but permanent tools of modern economic management.

Eccles’s significance lay less in theory than in execution. He helped convert Keynesian ideas from abstract economics into operational policy—argued in cabinet rooms, defended before Congress, and implemented through federal institutions. In doing so, he challenged both Wall Street orthodoxy and political caution, alienating bankers and fiscal conservatives who saw his views as dangerously inflationary.

Centralizing Power in a Fragmented System

Eccles’s most lasting institutional achievement was the transformation of the Federal Reserve itself. Before the New Deal, the Fed was a loosely coordinated network of regional banks, heavily influenced by private financial interests and often incapable of decisive national action. During the early years of the Depression, this fragmentation proved disastrous.

Through the Banking Act of 1935, Eccles helped centralize authority in the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, strengthening the role of the chair and laying the groundwork for coordinated national monetary policy. This reform shifted power away from regional and private actors toward public accountability, converting the Fed into a modern central bank capable of responding to systemic crises. Much of the Fed’s contemporary structure—including the balance between independence and coordination—can be traced directly to this moment.

Why Central Banking Could Never Be Neutral

Unlike many central bankers before or after him, Eccles rejected the notion that monetary policy was a neutral, technocratic exercise. He believed central banking was inherently political in its consequences, shaping employment, wages, and economic security. Price stability mattered—but only insofar as it supported full employment and mass consumption.

For Eccles, monetary and fiscal policy had to work together. Interest rates, public spending, and taxation were instruments to be aligned in service of broad prosperity. An economy that delivered stable prices alongside persistent unemployment, he argued, had failed its citizens.

War Finance and the Cost of Commitment

During World War II, Eccles supported policies that subordinated monetary independence to wartime necessity, including low interest rates to facilitate massive federal borrowing. These choices helped finance the war effort but later exposed him to criticism as inflation pressures emerged. In the postwar years, as political consensus shifted and fears of inflation replaced fears of depression, Eccles increasingly found himself isolated.

By the late 1940s, advocates of restraint and central bank independence regained influence. Eccles left the Federal Reserve in 1948, out of step with a policy establishment eager to return to orthodoxy and suspicious of sustained government intervention in peacetime.

The Limits of Demand Management

Eccles was not without blind spots. He underestimated the political resistance to permanent deficit spending and overestimated the durability of New Deal consensus. His framework did not fully anticipate the challenges of inflationary pressure, supply-side constraints, or global capital mobility. More fundamentally, his model relied on a level of political agreement that proved fragile once crisis conditions faded.

These limitations, however, reflect the changing terrain of postwar economics rather than a failure of Eccles’s core insight. He correctly identified that mass prosperity required active stabilization—and that markets alone could not guarantee it.

The Enduring Question of Monetary Power

Marriner Eccles stands as a pivotal architect of modern American economic governance. He legitimized the idea that government could—and should—act decisively to stabilize the economy, using fiscal and monetary tools in concert. In reshaping the Federal Reserve and embedding Keynesian logic into U.S. institutions, he permanently altered the boundaries of economic policy.

Today, as central banks grapple with inequality, financial fragility, and renewed coordination with fiscal authorities, Eccles’s legacy feels strikingly current. His question remains unresolved: should economic policy serve abstract financial norms, or should it be judged by its capacity to sustain broad employment and shared prosperity? Eccles answered decisively—and forced American monetary policy to confront its social responsibilities.