The Populist Who Terrified a President: Huey Long’s War on Wealth

Huey Long emerged during the Great Depression as one of the most electrifying and polarizing figures in American politics. At a time when economic collapse shattered trust in institutions, Long positioned himself as the uncompromising voice of the “forgotten man.” His message blended genuine concern for economic suffering with a confrontational style that thrilled supporters and terrified opponents. Few figures of the era so directly challenged both Wall Street and the sitting president from the left.

Born into a modest rural family in Louisiana, Long cultivated a deep resentment toward elites and professional classes. He styled himself as a self-made man who understood poverty not as theory but as lived experience. This background shaped his lifelong hostility toward concentrated wealth and inherited privilege. Long’s political identity was rooted in personal grievance transformed into mass appeal.

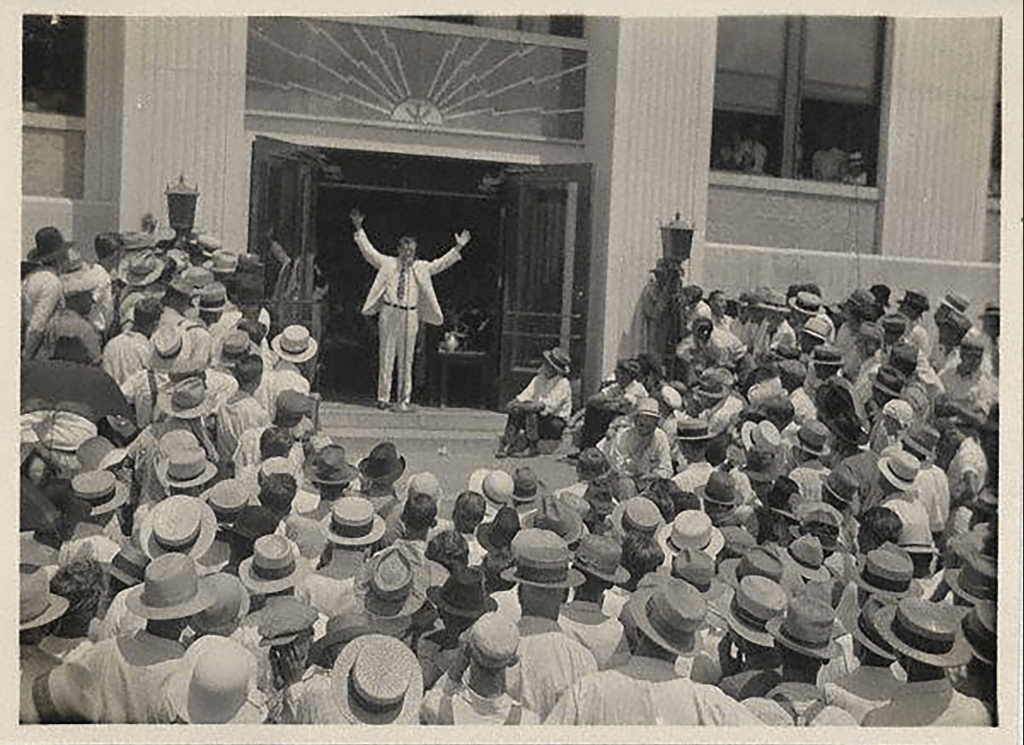

Long’s rise began in Louisiana state politics, where he mastered populist rhetoric and political combat. As governor, he promised roads, schools, and hospitals for ordinary citizens who had long been neglected by state government. His speeches were theatrical, filled with humor, anger, and moral outrage. Voters responded to his certainty in an era defined by doubt.

The Great Depression gave Long a national stage. As unemployment soared and banks failed, Long argued that the crisis was not accidental but structural. He insisted that the economy was collapsing because too much wealth was concentrated in too few hands. To Long, inequality was not a side effect of capitalism but its central flaw.

This diagnosis led directly to his most famous proposal: the “Share Our Wealth” program. Long called for heavy taxes on large fortunes, inheritances, and incomes above a set ceiling. The redistributed wealth would guarantee every American family a minimum income, housing, education, and economic security. His slogan—“Every man a king, but no one wears a crown”—captured both his egalitarian promise and his personal flair.

Share Our Wealth was not merely a policy proposal but a political movement. Long organized thousands of clubs across the country, claiming millions of supporters. These clubs functioned as grassroots pressure groups, spreading his message through meetings, pamphlets, and radio broadcasts. Their rapid growth signaled widespread dissatisfaction with existing reforms.

Initially, Long supported Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, seeing it as a step in the right direction. Over time, however, his support turned to bitter opposition. Long accused Roosevelt of protecting bankers and industrialists while offering only temporary relief to the poor. He argued that the New Deal stabilized capitalism instead of dismantling its inequities.

Long’s critique of Roosevelt was especially threatening because it came from the left. Conservatives opposed the New Deal on ideological grounds, but Long attacked it for not going far enough. He framed Roosevelt as timid, compromised, and captive to financial elites. This positioned Long as a rival populist with a more radical vision of redistribution.

Roosevelt took Long seriously as a political threat. Privately, the president and his advisors viewed Long as one of the most dangerous figures in American politics. The fear was not just electoral competition, but the destabilizing effect of Long’s rhetoric on democratic norms. Long’s popularity demonstrated how fragile political legitimacy had become.

Yet Long’s populism carried an authoritarian edge. In Louisiana, he centralized power aggressively, dominating the legislature and silencing opposition. He rewrote state laws to consolidate control and used patronage to reward loyalty. Critics argued that he ruled the state like a personal fiefdom.

This contradiction lay at the heart of Long’s legacy. He spoke passionately about democracy and economic justice while undermining institutional checks and balances. His supporters defended his methods as necessary to overcome entrenched corruption. Opponents warned that his disregard for limits foreshadowed dictatorship.

Long’s use of mass communication amplified both his appeal and his danger. Through radio broadcasts, he reached millions directly, bypassing traditional political gatekeepers. His style was emotional and confrontational, emphasizing moral clarity over nuance. In an age of radio, charisma became a political weapon.

The international context made Long’s rise even more unsettling. Across Europe, economic crisis was fueling authoritarian movements that promised order and redistribution. Critics worried that Long represented an American version of this trend. The fear was not simply what Long proposed, but how he wielded power.

Long openly contemplated a presidential run in 1936. He believed his Share Our Wealth platform could mobilize the poor against both major parties. Even without winning, he could split Roosevelt’s coalition and destabilize the election. His ambition added urgency to the controversy surrounding him.

In 1935, Huey Long was assassinated in the Louisiana state capitol. His death abruptly ended his national challenge and plunged his supporters into mourning. The assassination removed a volatile force from American politics at a critical moment. It also left unresolved questions about what his movement might have become.

In the aftermath, Roosevelt moved to strengthen and expand New Deal programs. Some historians argue that Long’s pressure helped push the administration toward more progressive taxation and social welfare. Whether intentionally or not, Long influenced policy by threatening political upheaval. His presence reshaped the boundaries of acceptable reform.

Long’s legacy remains deeply contested. To admirers, he was a fearless champion of economic justice who dared to confront entrenched wealth. To critics, he was a demagogue whose methods endangered democracy. Both interpretations contain elements of truth.

What is undeniable is that Long gave voice to genuine suffering. Millions of Americans felt excluded from recovery and betrayed by elites. Long articulated their anger with clarity and force. His popularity revealed the depth of despair beneath the surface of the New Deal era.

At the same time, Long’s career illustrates the risks of populism in moments of crisis. Economic desperation can legitimize extraordinary power and justify the erosion of democratic norms. Long blurred the line between reform and domination. His story is a warning as much as an inspiration.

Huey Long remains one of the Great Depression’s most unsettling figures. He challenged Wall Street, confronted Roosevelt, and proposed a radically different vision of American equality. Yet his legacy forces an uncomfortable question: how far can democracy bend in the pursuit of justice before it breaks? In that tension lies the enduring fascination—and danger—of Huey Long.