1937 - A Crucial Turning Point in the Shadow of the Great Depression

The year 1937 sits at a pivotal juncture in American and global history, shaped profoundly by the lingering effects of the Great Depression. While the U.S. economy had shown signs of recovery from the crash of 1929, 1937 witnessed a sudden reversal—often termed the “Roosevelt Recession”—that reignited unemployment, stalled industrial output, and cast doubts on the durability of the New Deal’s gains. This year marked not only a critical economic setback but also a significant period of social, political, and cultural transformation, all of which remained deeply entangled with the era's broader economic turbulence.

I. Background: The Great Depression’s Long Shadow

The Great Depression, triggered by the 1929 stock market crash, had by 1933 plunged the U.S. into its worst economic crisis. Unemployment soared to 25%, banks collapsed, and industrial output fell by nearly 50%. The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 brought a wave of reforms under the New Deal—Social Security, job creation programs like the WPA and CCC, banking reforms, and new labor protections—all designed to stabilize the economy and restore public confidence.

By the mid-1930s, some signs of recovery emerged. Unemployment had dropped to around 14% by 1936, industrial production was climbing, and the gross national product was rebounding. Yet the underlying fragility of the economic system meant that any premature withdrawal of support could reignite crisis—a reality that would be painfully confirmed in 1937.

II. The 1937 Recession: A Self-Inflicted Wound

In early 1937, President Roosevelt, concerned about rising federal deficits and emboldened by the Democratic landslide in the 1936 election, sought to rein in government spending and balance the budget. This decision was driven by political and ideological pressure, including from fiscal conservatives and business interests wary of expanding federal power.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy, doubling reserve requirements for banks in an attempt to forestall inflation. These twin moves—reduced government spending and a contractionary monetary policy—proved disastrous.

Economic Consequences:

Unemployment surged again, rising from 14.3% in 1937 to nearly 19% by 1938.

Industrial production dropped by more than 30% between August 1937 and March 1938.

The stock market plunged—the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell nearly 50% from its 1937 peak.

Wages stagnated or fell, and many public work programs were curtailed just as they were beginning to stabilize communities.

The recession of 1937 was, in many ways, a policy-induced relapse. Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman later described it as the result of "the most dramatic tightening of monetary and fiscal policy in the history of the United States."

"The 1937 recession serves as a textbook example of how overcorrecting too early in a recovery can trigger renewed collapse," says Henry Waldron, an economist and historian at Defined Benefits. "It was a premature victory lap that turned into a painful rerun of Depression-era suffering."

III. Political Ramifications and the New Deal’s Future

1937 also marked a shift in the political terrain. Roosevelt, fresh off a landslide victory, overplayed his hand with a controversial plan to “pack” the Supreme Court. Frustrated by the Court striking down several New Deal laws, he proposed expanding the Court to allow for up to six new justices. The proposal was met with fierce opposition from both Republicans and Democrats, ultimately failing but permanently damaging Roosevelt's political capital.

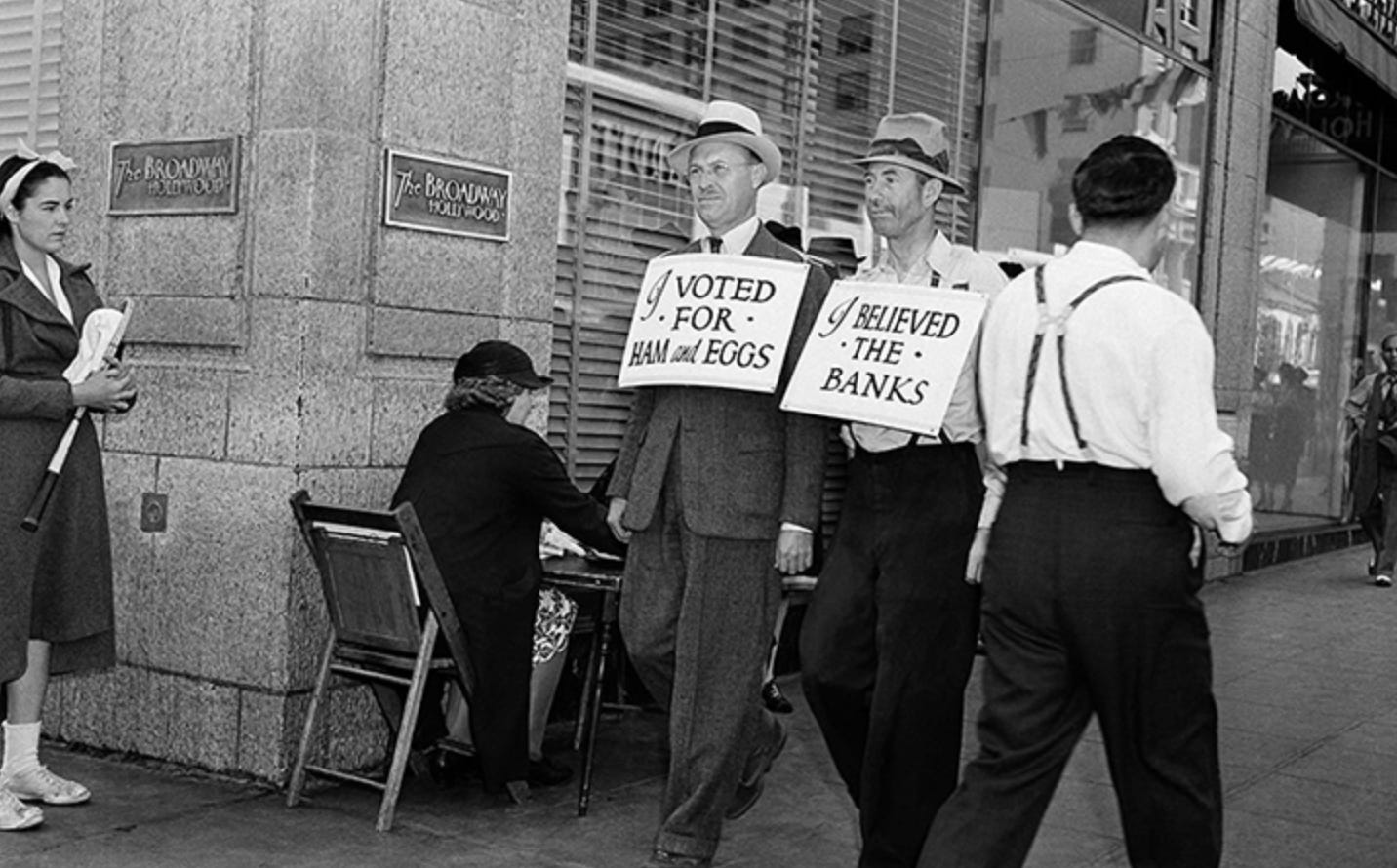

Meanwhile, public frustration mounted as the 1937 downturn erased hard-won gains. Conservatives used the recession to argue that the New Deal was ineffective or even harmful. Business leaders warned of creeping socialism, and the American Liberty League—a coalition of business interests and conservative Democrats—gained traction in its opposition to government intervention.

Despite the pushback, Roosevelt eventually reversed course. In 1938, new public spending was injected into the economy through a $3 billion relief package, and the recession began to ease by mid-1939. The Court, meanwhile, gradually began upholding New Deal legislation, with key justices shifting their stance in what became known as “the switch in time that saved nine.”

IV. Labor Unrest and the Rise of Union Power

The economic decline of 1937 also intensified labor unrest. Despite the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) in 1935, which guaranteed workers the right to unionize and bargain collectively, implementation was uneven. Business resistance remained fierce, and violence often broke out in response to labor organizing.

A significant event in 1937 was the Memorial Day Massacre in Chicago. On May 30, police opened fire on striking steelworkers outside the Republic Steel plant, killing 10 and injuring dozens. The violence shocked the nation and highlighted the precariousness of labor rights, even after legal protections had been established.

Meanwhile, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), founded in 1935, expanded its influence by organizing unskilled and semi-skilled workers in major industries. General Motors, after a 44-day sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan, recognized the United Auto Workers (UAW) in early 1937—a major milestone in labor history.

But the economic downturn weakened union momentum. As unemployment rose again, labor’s leverage shrank, and strike activity declined by late 1937. Still, the groundwork had been laid for the surge in union membership and activism that would characterize the 1940s.

V. Global Implications: Depression and the Drift Toward War

While 1937 was critical domestically, its significance also extended globally. The Great Depression had destabilized economies and governments worldwide, and by 1937, the consequences were becoming dire:

In Germany, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime continued its militarization and suppression of dissent, feeding on economic nationalism and resentment from the Treaty of Versailles.

Japan, facing economic stagnation and resource scarcity, invaded China in July 1937, initiating the Second Sino-Japanese War—a conflict that would merge with World War II just two years later.

In Spain, the Spanish Civil War raged between Republican forces and fascist troops led by Francisco Franco, with Hitler and Mussolini supplying arms and support to the latter. Many Americans, including writers and veterans from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, volunteered to fight on behalf of the Spanish Republic, seeing it as a bulwark against fascism.

“The collapse of global trade and confidence in the early 1930s didn’t just bring down markets—it destabilized democracies,” explains Mr. Waldron. “1937 saw that instability take root and spread, especially in regimes already veering toward militarism or authoritarianism.”

Thus, the instability born of the global Depression helped pave the way for authoritarianism, militarism, and war. The economic desperation of the 1930s eroded faith in democratic institutions in many countries and contributed to the collapse of international cooperation.

VI. Arts and Culture: Creativity Amid Crisis

Despite the economic downturn, 1937 was a flourishing year for American culture—often spurred by New Deal programs like the Federal Writers’ Project and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). These programs put artists, authors, and performers to work, creating enduring legacies in literature, theater, and visual art.

Key cultural highlights of 1937 include:

Literature: John Steinbeck published Of Mice and Men, a story shaped directly by the Depression’s themes of dislocation, labor exploitation, and friendship under hardship.

Film: Walt Disney released Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the first full-length cel-animated feature film, revolutionizing animation and becoming a massive box office success. The film was a rare escapist triumph amid a grim economic landscape.

Music: Swing and jazz dominated the airwaves, providing an upbeat counterbalance to the somber realities of the economy. Big bands led by Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Count Basie helped lift the public spirit.

Art and culture in 1937 acted as both reflection and refuge. Many works directly addressed the Depression’s injustices; others offered fantasy and escape from daily struggle.

VII. The Road Ahead: Recovery and War

By the end of 1937, it was clear that the Depression’s grip had not fully loosened. The year’s recession forced a re-evaluation of economic policy, ultimately strengthening the argument for sustained public investment and expanded government oversight. This recognition would shape policy decisions in the lead-up to World War II, which would become the true engine of economic revival.

As the 1940s approached, the world was on the brink of cataclysm. The Depression had disillusioned millions and redrawn political lines across the globe. Yet, in the United States, it also catalyzed the construction of a new social safety net, altered the relationship between government and citizens, and redefined the meaning of economic rights and security.

Conclusion

The year 1937 exemplifies the complex legacy of the Great Depression. It was a year of premature optimism dashed by economic miscalculation, of political missteps with long-lasting consequences, and of cultural and social vibrancy amid deep insecurity. Far from marking an end to the Depression, 1937 revealed the fragility of recovery and the enduring need for bold, informed economic leadership.

As economist Paul Krugman later remarked: “1937 is a cautionary tale of what happens when policy makers mistake a fragile recovery for a robust one.” It is a reminder that the journey out of economic crisis is not always linear—and that the cost of retreat can be high.